World

Unknown Scots soldiers given military burial in France

Two unknown Scottish soldiers killed in World War One have been laid to rest in France after their bodies were found during work to build a hospital.

War detectives from the Ministry of Defence (MoD) were called in to try and trace the identities of the two men, who were thought to have died during the Battle of Loos in 1915.

They were among more than 40 soldiers whose remains were interred during a ceremony in the town, near the city of Lille, on Wednesday.

Hundreds of people, including Princess Anne, attended the burial service, organised by the MoD’s Joint Casualty and Compassionate Centre (JCCC) and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC).

The battle, which saw British, Indian and French troops attempt to break through German defences in Artois, was the largest British attack of that year.

However, the attack was contained and repelled by German forces.

More than 59,000 soldiers from Britain and India died between 25 September and 8 October – an estimated 7,000 of whom were Scottish.

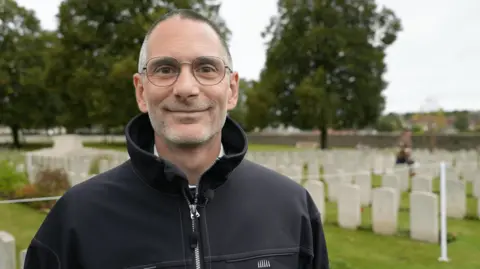

Tracey Bowers’ official title is head of commemoration with the JCCC.

However, she told BBC Scotland News her role was better known as “war detective”.

She is part of a team using a number of methods – ranging from regimental shoulder patches on uniforms to DNA testing – to uncover the stories of those who fell in battle and then reunite them with their families.

Items of clothing show that one of the two soldiers was a member of the Black Watch.

But she said that, on this occasion, it was not possible to find enough of a sample to “cross-match” with any living family.

“So many were killed were in the Battle of Loos, and so many Scottish soldiers in particular,” she said.

“If we can get a good DNA profile from that casualty, we would then look to go to families and then hopefully get a comparable match from families.

“They could be cousins, second cousins, nephews, nieces, great-nephews or nieces, and we will compare them against the DNA that we got from the soldier and hopefully we can then give a name to that casualty.

“We just haven’t been able to narrow it down, even though we tried to use DNA, the DNA we extracted from those remains was of such poor quality, we weren’t able to use it to cross-match with any family.”

Ms Bowers said remains were being uncovered on a daily basis in Northern France and Belgium during construction projects.

The process of identifying the dead can take months, or even years.

The team start with the location their bodies were found, then look at any artefacts that have been found on them.

Ms Bowers said it could offer families “closure” if they were aware of their relatives’ efforts during the conflict, or open a new strand to their family history if they did not know about their involvement.

“We are looking for things like regimental shoulder titles, cap badges, bits of uniform, bits of kilt, boots to show they are British,” Ms Bowers said.

“All of that narrows it down to hopefully the correct regiment. Then we look through war diaries to see that we had a regiment in that location at that time and then working out how many were missing from that regiment.

“Families either knew about that soldier and they have grown up knowing that their great-great grandfather was missing and killed in the war, or they knew absolutely nothing.

“But when they give us the DNA, they come on that journey with us for closure. I think they all become invested in the result.”

Dr Stephan Naji, head of recovery at the CWGC said about 80 sets of remains were found every year.

He said the number was increasing annually as more people become aware of their work.

Dr Naji said the “reflex” when remains are found at a construction site was to destroy them as it can slow down the project and add additional cost.

But he said retaining the bones could help his team extract and preserve them within a matter of hours.

He said: “We did major public awareness campaigns and now we are getting notifications on a regular basis.

“On a construction site, if they find bones, the reflex is to destroy them because it’s going to stop the construction site and that is going to cost money, they don’t want that.

“So my goal is to reassure everyone, whether they are deminers, archaeologists, construction workers; if you call us, we are on site within two hours and we clear the site by the end of the day.”

Major Paddy Marshall, from the 3rd Battalion, the Royal Regiment of Scotland, took part in the ceremony.

“It’s very humbling to be part of the service, but it is also very reassuring,” he said.

“As a long-term serving soldier, you can rest assured that if we fall anywhere in the world, at any time, someone will be there to remember you and that’s quite poignant.

“There is always the regimental family.”

Further remains discovered at the same site have been identified and DNA testing is under way to trace families.

All are interred with full military honours in ceremonies featuring a rifle salute and current soldiers from Scottish regiments.

Ms Bowers said the work would never stop until all the soldiers were accounted for.

“I don’t think this work will ever stop,” she said. “There are still half a million missing from the Second World War that are being recovered on a daily basis from Northern France and Belgium,” she said.

“We go all the way through to the end result where we work with current regiments to bring together a fantastic, poignant ceremony where they are laid to rest with full military honours.”

Soldiers at last among friends

From Cameron Buttle in Loos

Since dawn broke this morning an honour guard has stood over the coffins of two unnamed soldiers of Scotland, heads bowed, rifle barrel pointed to the ground.

It’s estimated that 30,000 soldiers from famous Scottish regiments like the Cameron, Gordon and Seaforth Highlanders fought in the battle of Loos more than 100 years ago. Seven thousand of them were killed.

More remains have been found nearby recently and many of them have been attributed to Scottish units, the work of the ‘War Detectives’ is already underway to try and identify them.

In the Loos cemetery alone the names of more than 22,000 soldiers whose bodies were never found are recorded, an indication of how difficult the task is for the war detectives.

Whatever the outcome they will all be buried with full military honours in this cemetery and, as one grave stone inscription reads, they will be “at last among friends”.