Paris Gourtsoyannis

World

Scotland’s independence referendum ten years on

A decade ago today, Scots were asked to make one of the most important choices of their lives.

Did they agree that Scotland should be an independent country – Yes or No?

It was a question that appeared straightforward enough but one enveloped by passionate opinions and a fevered referendum campaign that dominated all realms of Scottish public life.

So much has happened since that seismic vote. The UK has left the European Union, the world grappled with the coronavirus pandemic and war has returned to Europe.

The issue of Scottish independence hasn’t gone away either, with opinion polls broadly showing an almost even split between Yes and No.

STV News takes a look back to when the issue of Scottish independence was the burning issue of the day, and Scotland found itself at the heart of the international news agenda.

How did the referendum come about?

In May 2011, the SNP sent shockwaves across Scotland’s political landscape.

The party won an overall majority at Holyrood in a landslide victory that paved the way for a new chapter in Scotland’s long-running debate over its constitutional future.

STV News

Alex Salmond, then First Minister, told STV News the sizeable majority was a mandate for a referendum on Scottish independence.

“Now, it wasn’t plain sailing because obviously there were lots of blocks and tackles, and nefarious activity and perfidious reasoning from Westminster,” he said.

“I mean, for example, they wanted two referendums at one stage, but through negotiations we got to a settlement.”

Former Scottish Conservative leader Ruth Davidson agrees that a referendum became inevitable following the 2011 Holyrood ballot.

“To an extent, the SNP had broken the election machinery in Scotland – nobody had expected them to get a majority,” she said.

“Almost as soon as we saw there had been one, it became obvious there was going to be a referendum.”

STV News

STV NewsThe SNP government set about achieving its chief aim just months after the election.

That culminated in the autumn of 2014 with the publication of a consultation paper entitled “Your Scotland, Your Referendum”.

The official campaign for independence was now under way.

It brought together the Greens, the SNP, the Scottish Socialists, as well as celebrities including Alan Cumming and Martin Compston.

“It developed particularly in the summer of 2014 into very much being a grassroots, multifarious, groups of people springing up all over the place,” said Salmond.

Meanwhile, the broadcaster Lesley Riddoch remembers the moment as “releasing huge amounts of energy”.

“People started to reimagine would Scotland could be like,” she told STV News.

“All these organisations that just started to create themselves, whether it was Common Weal, Women for Independence, there was just loads. There were barking groups like ‘Otters for Yes’.

STV News

STV News“It was the release of pent-up stuff over decades, much longer for some people, and that felt incredibly exciting, unpredictable, there were a lot of meetings going on.

“A lot of people were well beyond their comfort zone and that was partly because the Yes campaign – the formal Yes campaign – was very slow to roll out materials, so eventually local Yes groups were being formed anywhere and everywhere.

“They just started producing their own stuff, so essentially that triggered the creation of lots of locally-centred groups, which are still running to this day.”

For the No side, Better Together was led by the former Labour Chancellor Alistair Darling.

He described the referendum as being the most important decision Scots would make in their lifetime.

STV News

STV NewsDavidson recalls: “There had to be quite a bit of work behind the scenes in terms of how it was going to work, because we had a coalition government in Westminster, so it was Conservative-Liberal Democrat, but the Labour Party in Scotland still thought of Scotland as theirs, they still had a lot of MPs there.

“A lot of egos had to be put to one side to make it happen and in terms of picking who ran it – it ended up being Alistair Darling.

“My understanding is that he wasn’t the first person who was approached from the Labour Party, but we knew it had to be a Labour person.

“If I look back at who was involved in those early days, it’s all people who have left us now.

“The Conservative voice on the board was David McLetchie, who died before the referendum. You also had Charles Kennedy from the Liberal Democrats. In many ways, it seems a very long time ago because the faces of Scottish politics have changed so much.

“I don’t know if Alistair wanted to do it, he’s never struck me as the sort of person who has pushed himself forward for anything, but he was an inspired choice.”

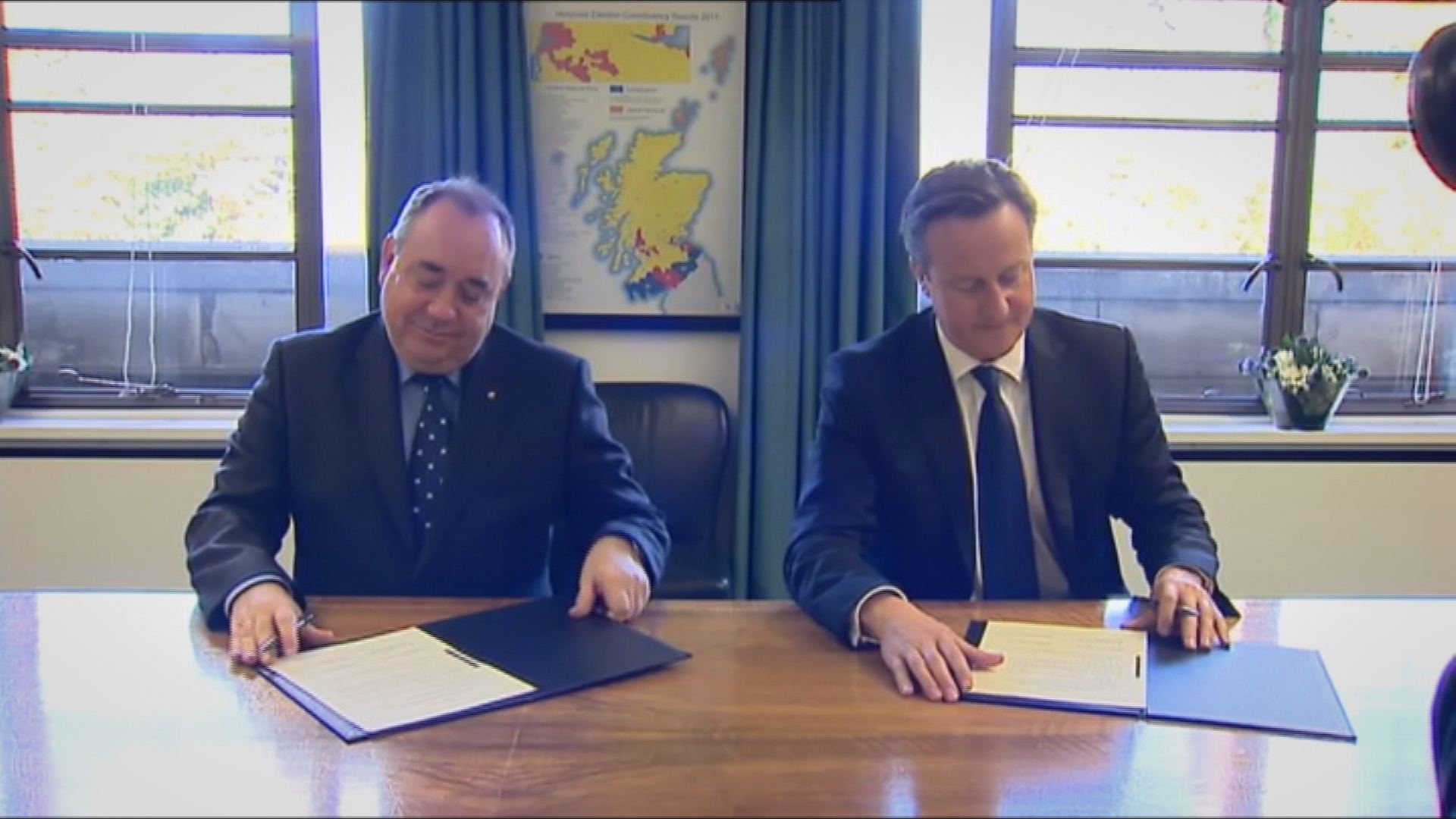

Edinburgh Agreement

In October 2012, Alex Salmond and then Prime Minister David Cameron met at St Andrew’s House in Edinburgh after months of negotiations between the UK and Scottish governments.

They signed the Edinburgh Agreement, giving the Scottish Parliament the power to legislate for a referendum.

The deal also handed Holyrood the decision over the timing of the vote, the franchise and the wording of the question on the ballot paper.

STV News

STV News“As you would expect there were a lot of attempts to gain advantage from Westminster,” explained Salmond.

“They wanted to set the terms of the referendum, but over the year and a bit of the negotiations we just held out.

“There was a very obvious argument if we were going to have a referendum on independence then it had to be born in Scotland, it had to be provided for by the Scottish Parliament.”

Cameron faced criticism – including from within his own party – with many believing he conceded too much to the Scottish Government during negotiations over the shape of the referendum.

“They got to choose the timing, they could pick the date, they got to choose the question, what the wording would be,” said Davidson.

“The one thing he (Cameron) really wanted was, the absolute red line, is that it had to be Yes/No and I think part of giving away so much in order to have that was it would be easy to understand and there would be a firm answer at the end of it, and once it was done, it was done.

“We know now that’s not the case but he wanted the result to be clear and he also didn’t want the nationalists, who have always sought grievance, to be able to say that in some way ‘this was rigged’.

“And I think giving away so much was almost a choice because he wanted them to have control over much of the process, so they can never say it was a rigged ballot in any way.”

It was agreed the referendum would be held on September 18 with a single question: Should Scotland be an independent country?

It would also see 16 and 17-year-olds in Scotland being allowed to vote for the first time.

STV News

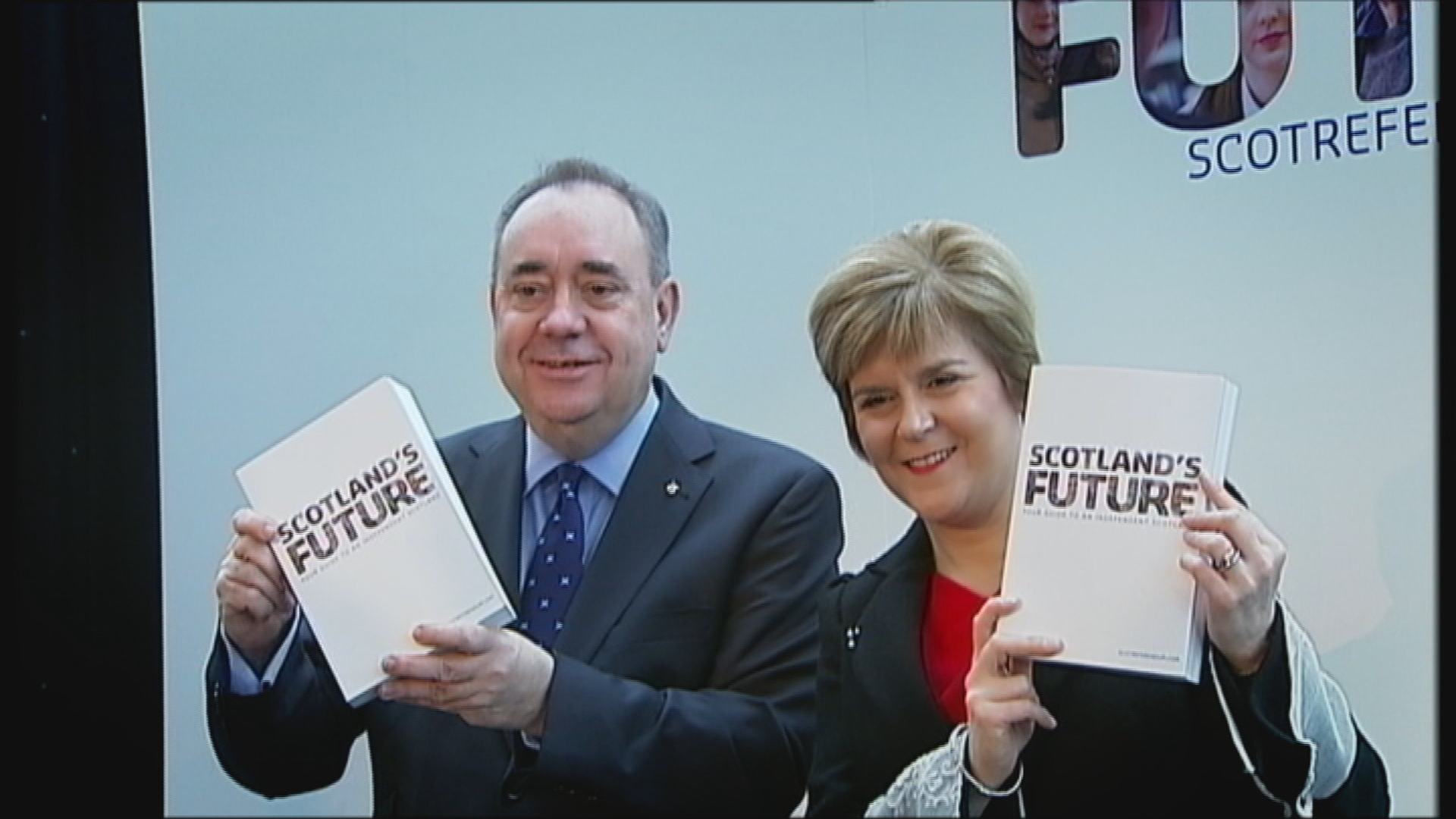

STV NewsOpinion was polarised across the country.

The UK Government published papers setting out the benefits for Scotland of being part of the union, and warned of the dangers of independence.

In response, the Scottish Government released its white paper, “Scotland’s Future”, which it said laid out a blueprint for a new state, promising a more prosperous and equal nation.

Television debate

STV secured the first live TV debate between Salmond and Darling.

It was a huge event with a peak audience of almost a million viewers watching on TV and a livestream failed to cope with demand from around the world.

A cross-examination section provided one of the biggest moments in the campaign. Darling said to Salmond: “Any eight-year-old can tell you the flag of the country, the capital of a country and its currency.

“Now I presume the flag is the Saltire, I assume our capital will still be Edinburgh, but you can’t tell us what currency you will have.”

That won the night for Darling after an unexpectedly lacklustre performance from SNP leader Salmond.

Former Labour MP Jim Murphy, a prominent No campaigner, said: “Of all the TV debates that have happened in modern British politics, the only one that’s had an impact, and I think a meaningful impact on the outcome, was that STV debate.

STV News

STV News“If only weeks before such a historic decision, you can’t be straight with the public as to what currency people would be spending then you don’t deserve to win.”

Davidson believes the STV debate was transformative in terms of hardening people’s views.

“We had gone into it with a bit of trepidation on our side,” she said.

“Alex Salmond was a big figure, he’s a bruiser in politics, he prides himself in being a fantastic debater and everybody thought he would wipe the floor with Alistair, and what we were hoping for was a score draw and that Alistair while quiet, and he is a quieter man, would be firm and solid and reassuring to people, as he had been during the financial crisis when he was chancellor.

“Actually, we got so much more from Alistair for that and he worked incredibly hard. He was prepping for days before and maybe I’m biased but I thought he won that debate.

“I think he was better than people thought he would be and I think Alex Salmond wasn’t as good as people thought he would be. He went on some flight of fancy about aliens and things and slightly lost the room, but also lost the television audience at home.

“I think it showed that actually Alex Salmond didn’t have all the answers and if they were serious about this, they needed to go away and do their homework – and they hadn’t done it. I think that debate and Alistair’s performance in it really did give us a bit of momentum, certainly gave us a lift in morale.”

Salmond recovered ground in a second head-to-head television debate and by now the whole campaign had engaged parts of the population previously disinterested in politics.

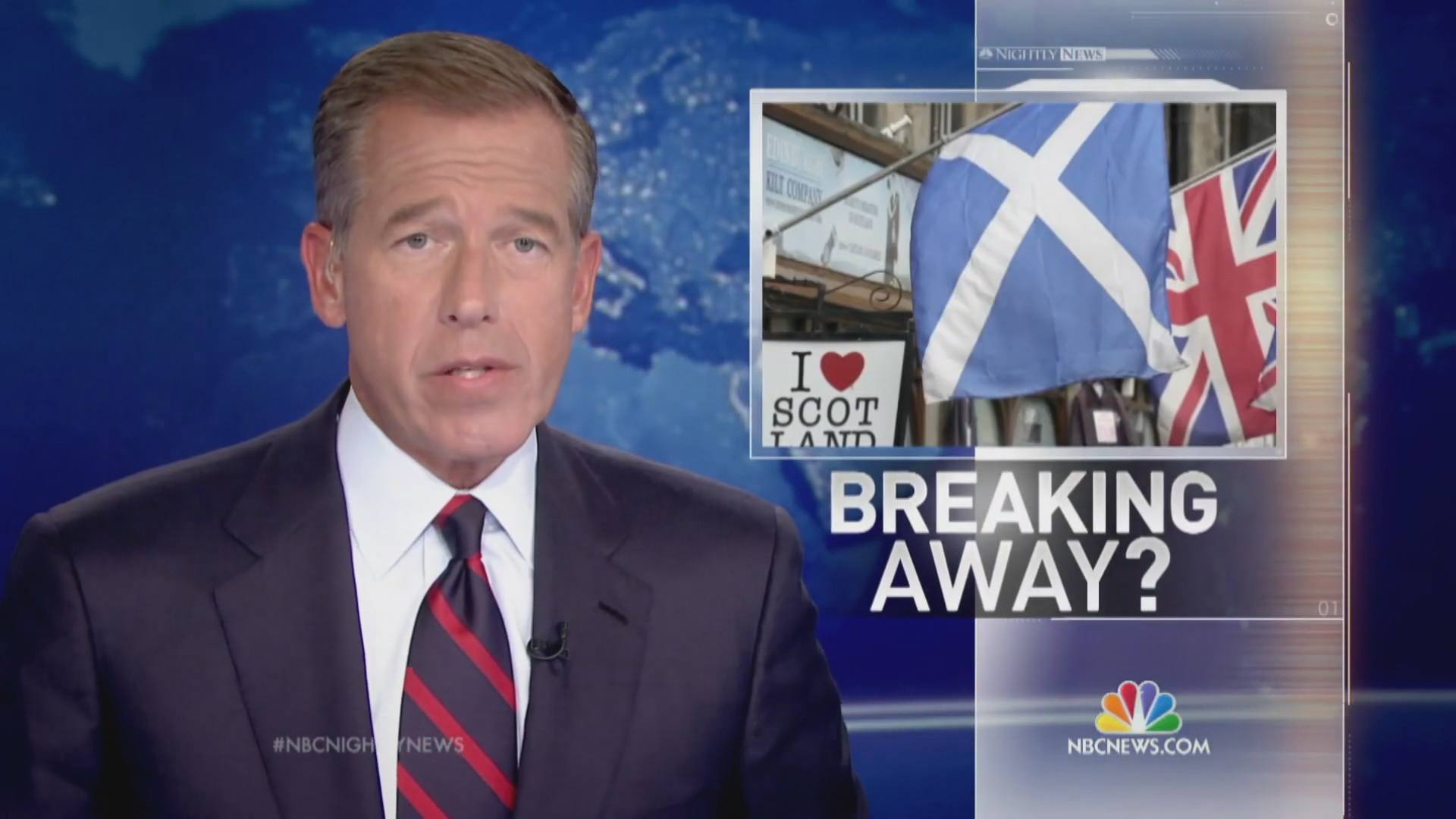

The debates made headlines around the world and campaigning in Scotland intensified as polling day drew ever closer.

“It felt big at the time, it felt Scotland was at the centre of politics for the world – not just for the UK. It was big politics,” said Davidson.

Yes takes the lead in poll

Less than two weeks before the vote, a Sunday Times poll put support for Yes in the lead for the first time.

“Obviously, we were delighted,” said Salmond. “It was the first poll of the campaign, and remember where we had come from, a long way back, showing Yes in the lead, so clearly it was a big boost

“I would be delighted if they (No campaign) had continued in their very overconfident, very, very negative campaign of running Scotland down – that would have been ideal if they had done that to polling day.

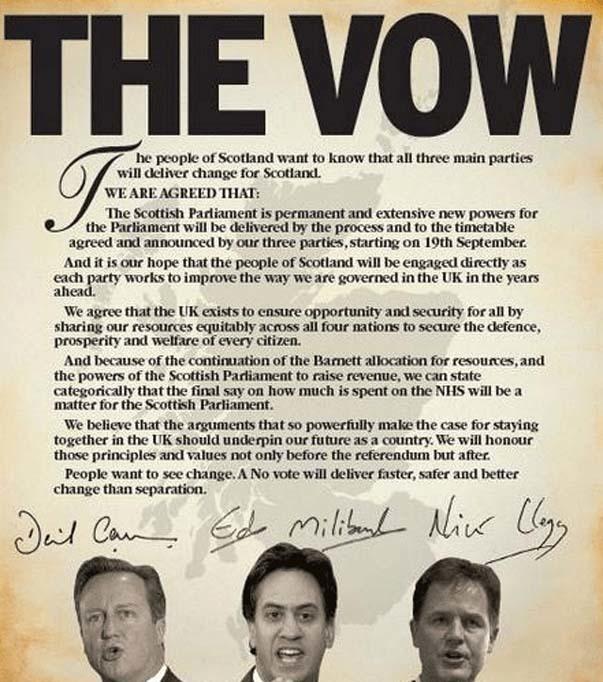

“But to be fair to them, they looked at that poll and suddenly realised they were in danger of losing and regrouped their campaign around what was called ‘The Vow’, which was basically a soft option – ‘We’ll give you anything you want, we’ll give you devo-max, you don’t have to risk independence’.”

The leaders of the main UK parties – Cameron, Ed Miliband and Nick Clegg – cancelled their appearance at Prime Minister’s Questions that week and travelled north to campaign.

Salmond said: “We treated that with some derision because it was quite funny, wasn’t it?

“But nonetheless it did show the establishment regrouping and perhaps if you had your time again I might have responded a bit differently to that last week of campaigning.”

Davidson said she was against the idea of the three main UK party leaders making a late visit to Scotland.

“Frankly, by that point in the campaign, I felt that looked a bit panicky, or like they had just noticed that this was about to happen because it was such a late decision.

“(I felt) all of these non-Scottish voices weren’t actually that helpful. I had argued that that shouldn’t happen but I was overruled.”

Referendum night

When the counting began, it soon transpired that voter turnout across the country was huge – reaching 84.5%.

Clackmannanshire Council – widely considered a bellwether local authority – was the first to declare and it was a victory for No.

“I thought we would just sneak it on polling day and it wasn’t really until the first result (that I thought otherwise),” Salmond said.

“It was Clackmannanshire, the wee county, which is interesting and often reflects Scotland.

Newsline Photos

Newsline Photos“I was in (Aberdeenshire restaurant) Eat On the Green in Udny Green in my constituency and Craig Wilson, the restauranteur had kindly given us the upstairs room for the last two hours of the campaign, I sat down and wrote a concession speech.

“I then went down to Edinburgh and made the concession speech. You waited until the other results came in obviously, you didn’t concede before it was mathematically impossible, and there was always lingering hope that the big Yes voting cities – Dundee and Glasgow – would weight the ballot back in our favour but I think in my heart I thought Scotland will likely follow Clackmannanshire once again.

“I had the thinking that somebody should take responsibility but I wasn’t under any pressure to stand down. Scotland rather likes people when they have been done down so it were, so there was a lot of feeling that the Yes campaign had been very unfairly treated, particularly by the BBC and the establishment mainstream media.

“It was an extraordinary thing that those who lost the referendum emerged as political winners, and those who won the referendum emerged as political losers.”

Victory was confirmed for the No side in the early hours of September 19. They had won by a margin of ten percentage points, by 55% to 45%.

Independence now

Salmond believes the decade since the referendum has been a frustrating period.

“I was pretty certain that the hard lifting had been done. Very few countries advance to that level of support for independence and then move back again, that’s almost unheard of.

“By and large, in terms of the polls for independence, that’s been the case. Independence has been knocking on 50% for the last ten years. What’s been missing is to arrange the political furniture in such a way as to force the issue and that’s partly been leading people up to the top of the hill, expecting a referendum, and then back down again, which has pretty disillusioned the Yes campaigners.

STV News

STV News“And partly it’s been the inability to unite the campaign behind a certain way forward, and also an inexplicable inability to seize opportunity.

“Above all, I think Scotland has been devoid of hope. The great thing about 2014 is that people had expectations, they had rising expectations, they had hope for the future of the country.

“That hope is in scarce supply now.”

For Davidson, however, the prevailing memory of the campaign isn’t one of hope, but of a bitter atmosphere that affected those involved.

“Sometimes it wasn’t a nice campaign to fight in,” she said. “I know different people have different memories of that but I particularly felt so sorry for some of our campaigners who were really struggling with the tone and the nastiness, and the edge and the malice they were being treated with during the campaign.”

Riddoch believes the No vote happened as a result of Scotland’s “deep-seated doubt about our own capacity”.

She said: “The more empowered people can be, the more they can see themselves doing stuff, the more it raises people’s ideas about what this country can be, so the only thing that mattered to me was to see people doing some heavy lifting and discovering that they could do it fine.

“The only issue that needed cleared up from a democratic point of view was whether Scots felt independence – the full bhuna – was what they needed to progress. There was an assumption given the way Scotland has been voting – I have to say since 1955, which has been progressive Labour or SNP – there was an assumption that devolution was just given, that was the standard, and we had a Scottish Parliament.

STV News

STV News“I did feel gutted and then you do feel this is playing into a classic Scottish trope of the many times that people have nearly made big changes in this country and just not quite. Fair enough, you just had to get to a stage of thinking, ‘OK, the thing I would take from all of that and which I think the subsequent years have proven is that it isn’t over’.

“It isn’t a phase, it isn’t a teenage preoccupation, it’s not a protest vote against any particular government, this is just a deep-seated belief that Scotland is a different country with a different political outlook and it doesn’t fit into a sort of adversarial Britain and that isn’t going away.”

A decade on from the vote to remain part of the United Kingdom, questions around Scotland’s constitutional future continue to colour the political debate.

However, the UK Government is refusing to budge in granting the power to hold a second referendum, and the Supreme Court has ruled that Holyrood can’t legislate without Westminster’s consent.

And with the once formidable might of the SNP taking a drubbing in July’s general election, the prospect of a second vote has slipped right down the political agenda.

The prospect of another referendum in the near future is growing increasingly unlikely. For some, that is a welcome development.

For others, there is lingering resentment that Scotland’s best chance of independence slipped through their grasp and the memories of the 2014 referendum still sting.

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country

Continue Reading