Football

Scotland’s 2024 General Election in numbers

By Philip Sim, BBC Scotland News

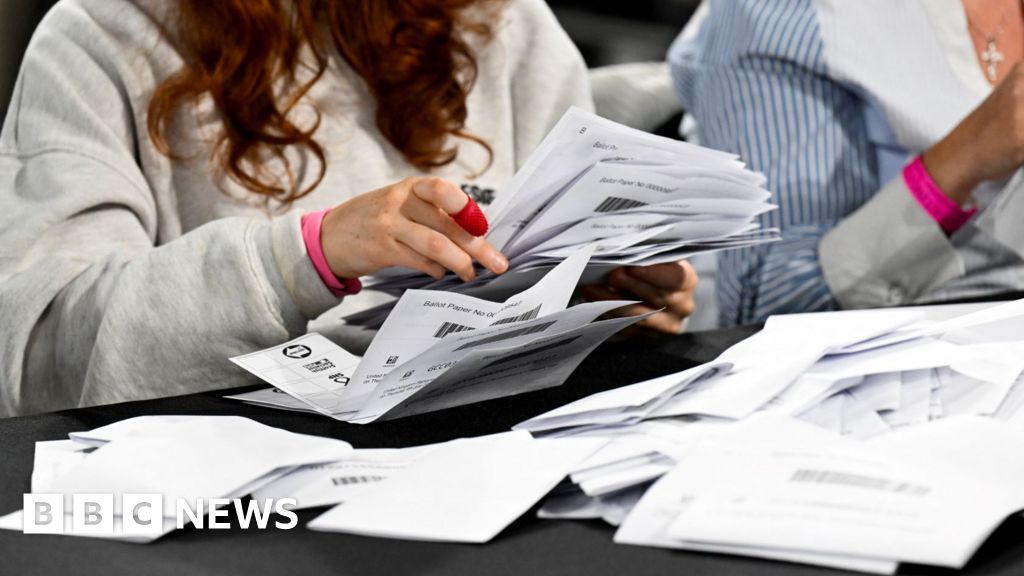

Reuters

ReutersThe obvious election headline in Scotland is Labour’s comeback amid an SNP collapse.

Labour gained 36 seats from the SNP to add to the one they had from 2019, sweeping their rivals out of the central belt.

The SNP is stuck on single figures, with nine – a huge fall – while the Tories and Lib Dems are on five each.

It’s worse for John Swinney than most polls had predicted, and indeed worse than his party could possibly have feared.

So what can we dig out of the results data which explains such a result?

Labour vote share up by 17 points

One easy explanation for improvement in a party’s fortunes is that more people vote for them.

Labour’s share of the vote went up enormously – up 17 percentage points, to 35.7%.

That’s higher than the 34.5% the party won in England, where their share ticked up by only 0.5 points.

While Sir Keir Starmer’s candidates down south profited chiefly from the Tory vote collapsing (they lost six million votes) and Reform UK surging, the picture in Scotland was a little more nuanced.

Here, there were two collapses to factor in.

SNP lose 500,000 votes

The SNP lost half a million votes, their share falling 15 percentage points to 29.9%.

Meanwhile, the Scottish Conservative share was almost halved, down 12.3 percentage points to 12.9%.

This was especially pronounced in central belt seats, and it was the combination of those two changes which boosted Labour to come through the middle.

In a number of seats they actually came from third place – consider East Renfrewshire, where Labour went from 12.4% of the vote to 43.7%, an incredible turnaround.

Lib Dems win 8.7% of seats with 9.1% of vote

One part of the story is the first past the post voting system.

In previous elections it’s helped sweep the SNP to crushing victories; now the all-or-nothing system has turned back to bite them.

Labour have won 65% of the seats in Scotland with 36% of the vote. The SNP meanwhile had 29.9% of the vote – but won 17.5% of the seats on offer.

The Lib Dems – ironically the greatest proponents of electoral reform – have had the closest to a representative result, with 8.7% of the seats (so far) from 9.1% of the vote.

The Tories returned the same share of seats with 12.1% of the vote.

Two party battle in most seats

There are other ways in which Scotland has become a contest between the SNP and Labour.

Other than the 10 seats held by the Lib Dems and Tories, almost every seat is now a contest between the SNP and Labour.

The Tories were in second place in 18 seats prior to this election; that figure is now down to five.

Two of those seats are pretty marginal – both of the Moray seats have an SNP majority of around 2.5%.

But otherwise there is a lack of clear targets for the Conservatives to build towards when they are planning their recovery.

Given the party is also looking for new leaders both at Westminster and Holyrood, and it’s clear the Tories are in a bit of a pickle.

Seven SNP seats among 10 most marginal

Scotland is no stranger to big swings in the vote; volatility is baked into our political DNA.

Consider that Lothian East has now returned a different MP at every election since 2005.

Meanwhile, Dundee Central has gone from being the safest seat in the country before the election, to the most marginal after it – now having a majority of just 1.7%, or 675 votes.

The SNP used to preside over big majorities, but now seven of its nine seats are among the 10 most marginal in Scotland. They only have two which could be considered safe, with a double-digit majority.

Lib Dems lost deposit in 28 seats

The Lib Dems now defend the safest seat in Scotland in Orkney and Shetland (majority 37.7%), and remain the absolute kings of localised campaigning.

They have three of the four safest seats in Scotland, with Edinburgh West and North East Fife also having majorities over 30%.

But they also lost their deposit in 28 seats, failing to break 5% of the vote.

It’s hard to call it a bad night for them, given the Lib Dems also hope to win the delayed count in Inverness, Skye and West Ross-shire – which would take their haul to six, trebling their representation on these new boundaries.

But like the Tories, they don’t have a lot of obvious target seats where they could spread their influence in future.

Tory vote less than 5% in Glasgow

Talking of deposits, the Conservatives lost 15 – up from zero in 2019, and a worse total than Reform UK, who only lost nine.

The Tories fell below 5% of the vote in all six of the Glasgow seats, the opposite of the performance of the Scottish Greens.

The party didn’t come close to winning any seats, but it did finish third in a couple in Glasgow – and in two, their share of the vote was greater than Labour’s eventual majority.

Obviously votes don’t belong to any one party and could break in unpredictable directions, but the SNP may be particularly rueing their fallout with their former governing partners in Glasgow.

The Greens meanwhile are delighted with their returns – having doubled the number of candidates they stood this year, they will feel they have carved out fresh footholds.

Alba’s 19 candidates secure just 11,784

Talking of splits in the pro-independence vote, one which decidedly did not materialise was in the role of Alex Salmond’s Alba Party.

Their 19 candidates didn’t crack 12,000 votes in total – the best performance coming from Neale Hanvey, who managed 2.8% in Cowdenbeath and Kirkcaldy, which he has represented for the last five years.

Three other former MPs – Kenny MacAskill, George Kerevan and Corri Wilson – failed to get above 1.5% of the vote.

Alba have their hopes chiefly pinned on the next Holyrood election, and its proportional representation system – but these kind of figures even make gains there look like a long shot.

A turnout of 59.2% was 8.5 points down on 2019

The key comfort for the SNP may be that this was a low-turnout election, with voter participation at 59.2%. That’s down 8.5 percentage points from 2019, and was reflected in every seat.

So when John Swinney is trying to work out where half a million votes went, he might conclude that many of them could have stayed at home.

The same thing hit the party in 2017, when they lost 21 seats – and many of them were won back in 2019, when turnout rose again.

So even hours after the counting has finished, most of the parties will already be turning their attention to the Holyrood election in 2026 – some looking to consolidate their gains, and others hoping to bounce back.