World

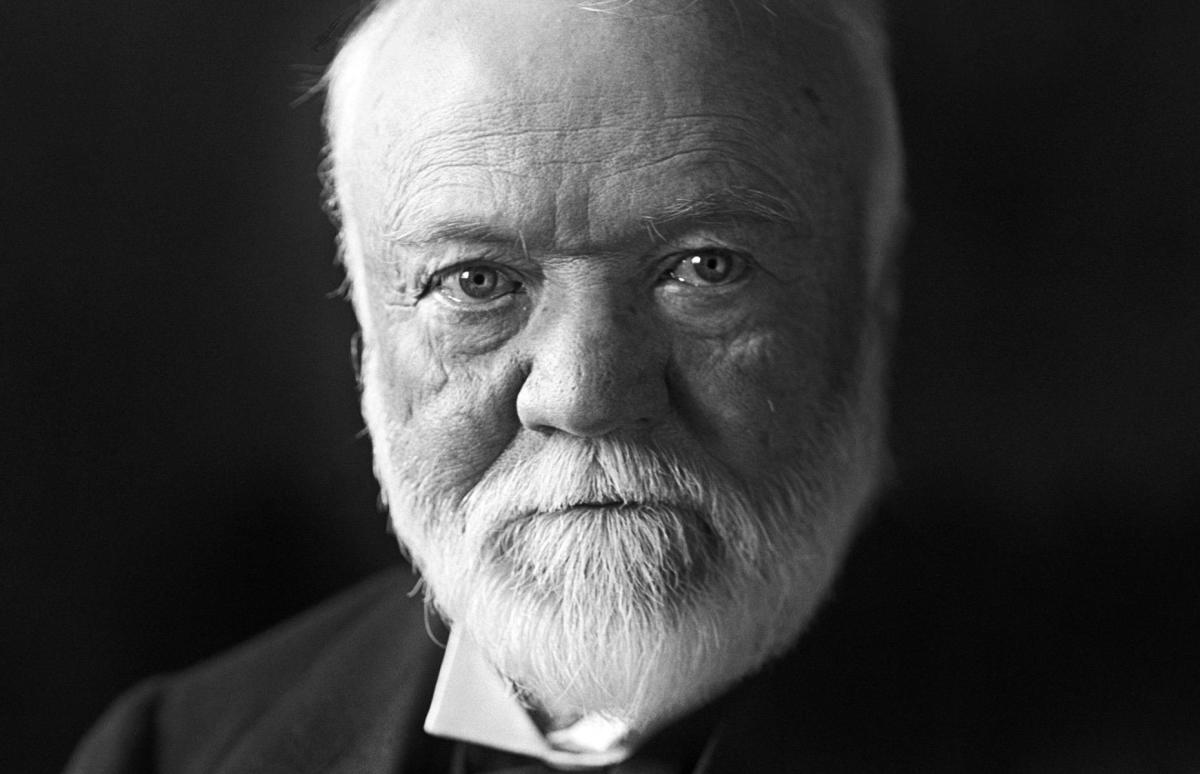

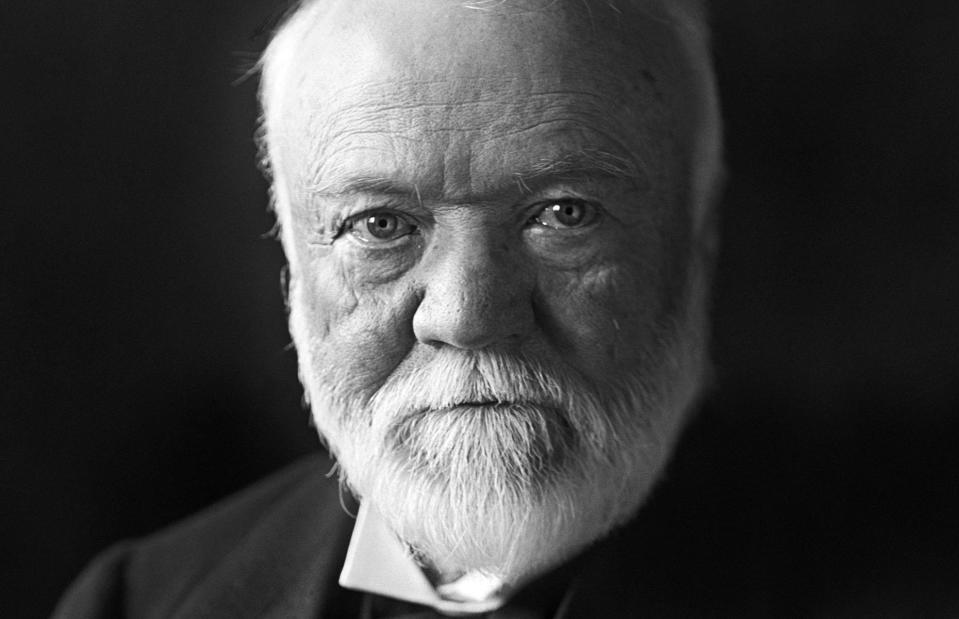

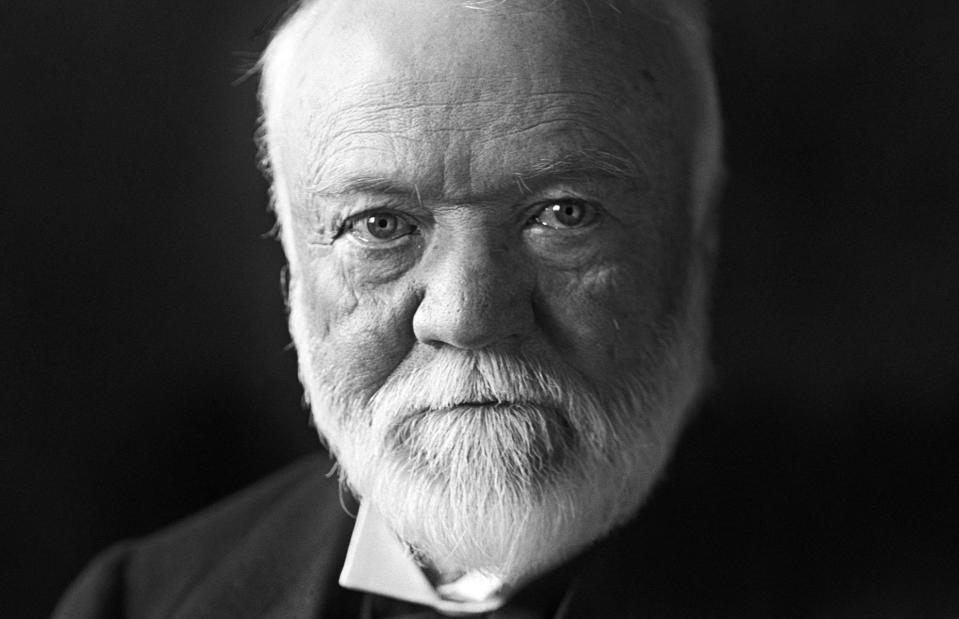

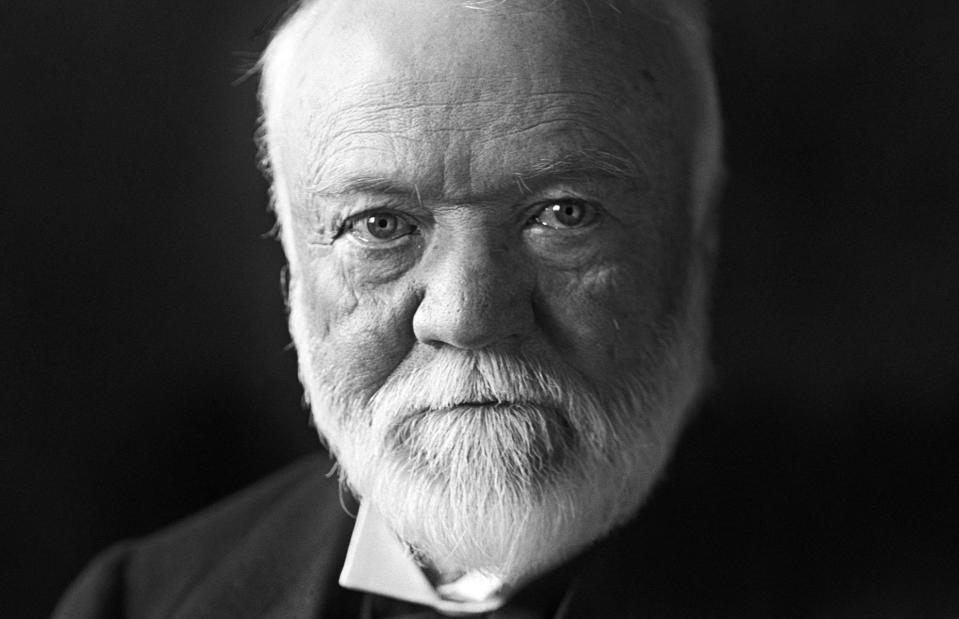

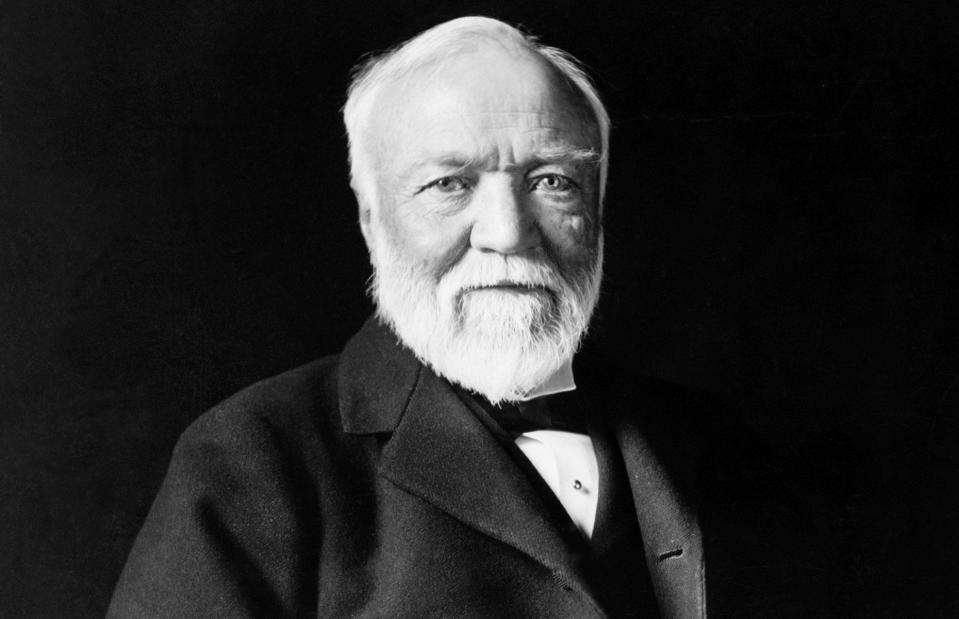

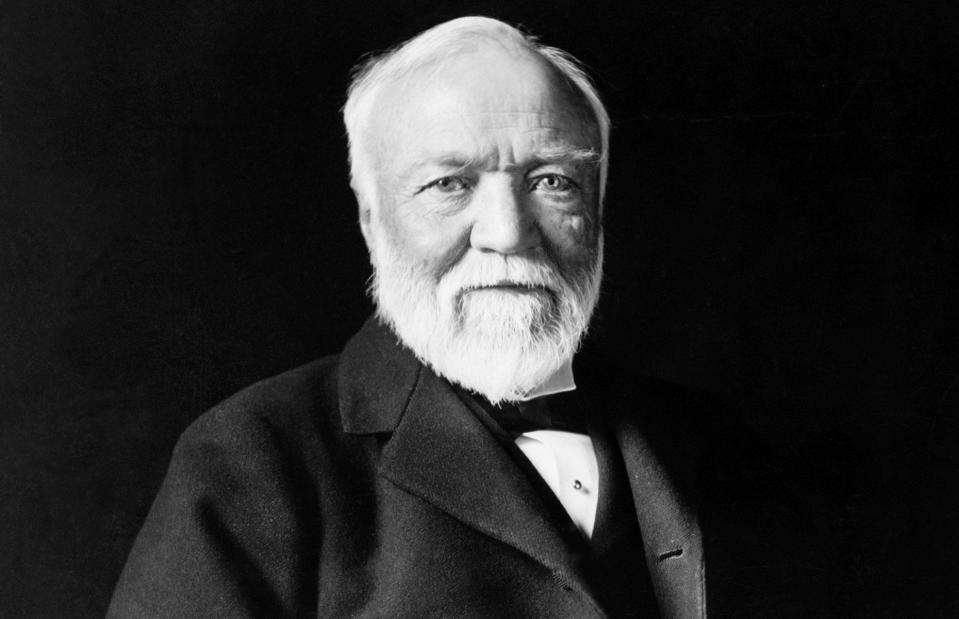

How a poor Scottish boy became the world’s richest man

The mega-wealthy Gilded Age icon who gave away his fortune

Archive Pics/Alamy Stock Photo

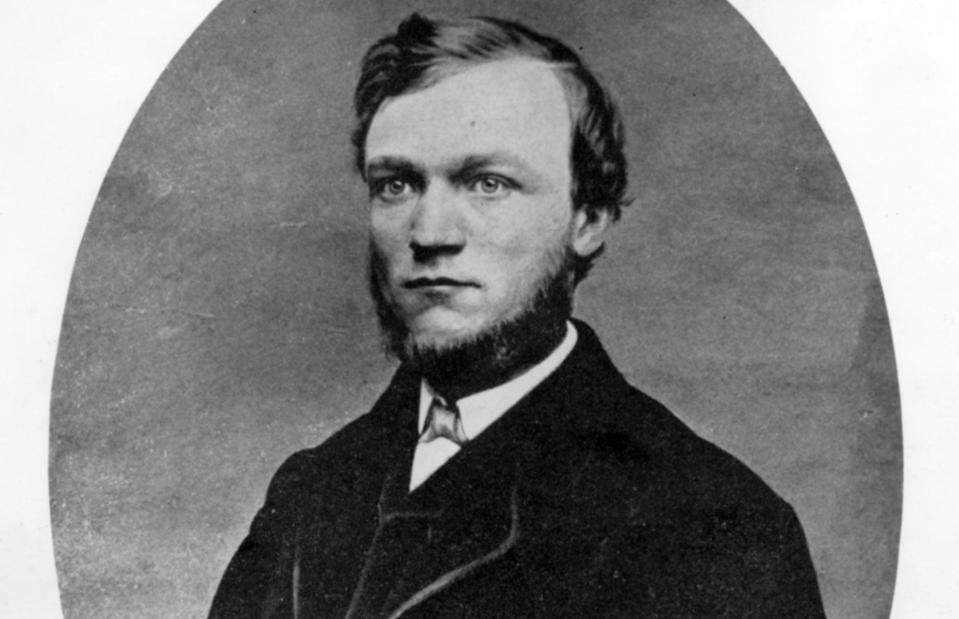

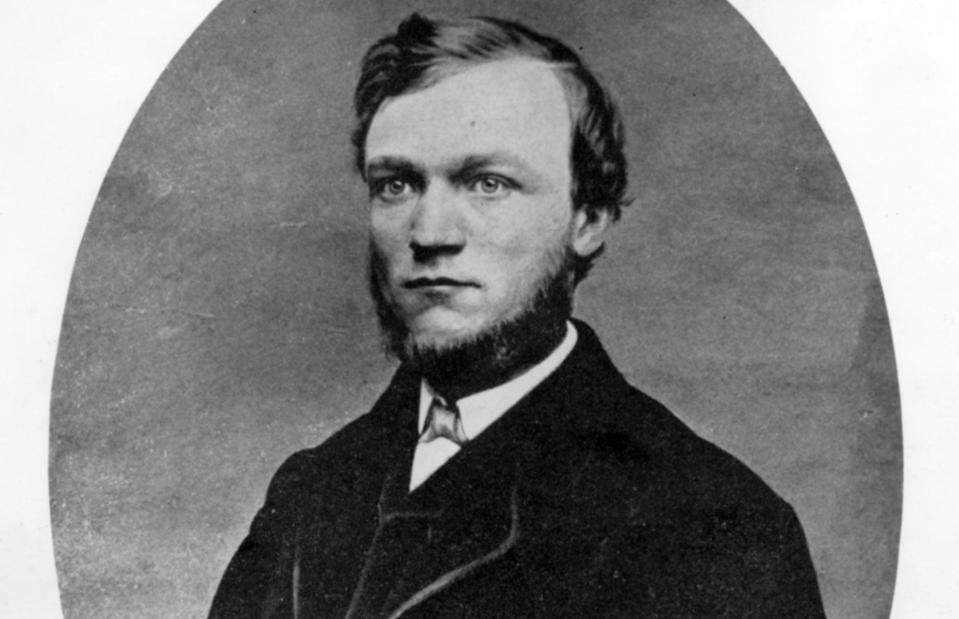

Fiercely ambitious and with the intellect and savvy to match, Andrew Carnegie left behind grinding poverty in his native Scotland at the age of 12 to start a new life in America.

Despite his impoverished roots, Carnegie became the world’s richest person. And unlike some other business tycoons of the Gilded Age period, Carnegie was as generous as he was successful, ultimately giving away his entire fortune.

Read on to discover the deep-pocketed tycoon’s incredible journey from poverty to prosperity.

All dollar amounts in US dollars

Humble beginnings

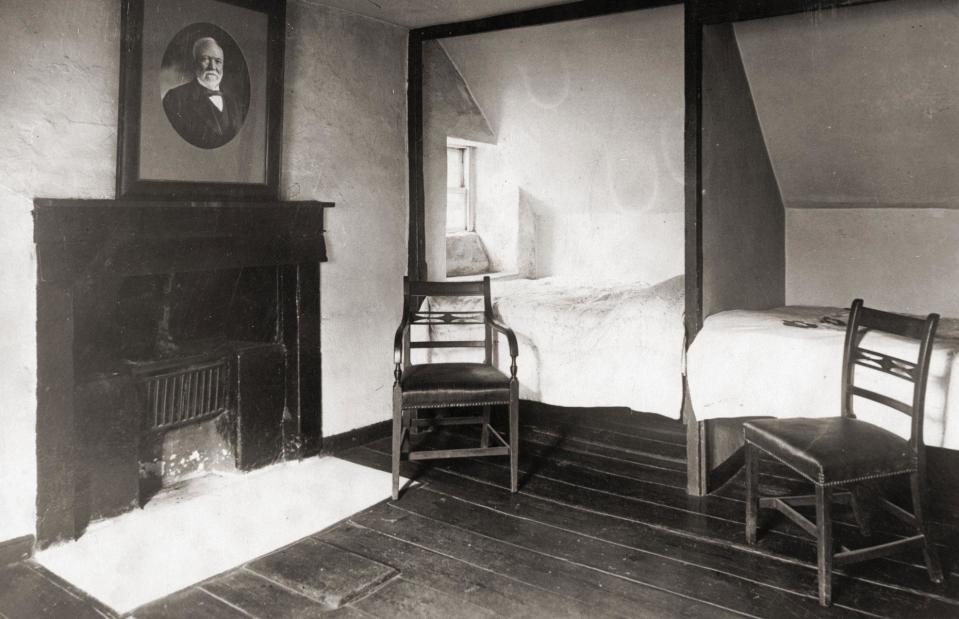

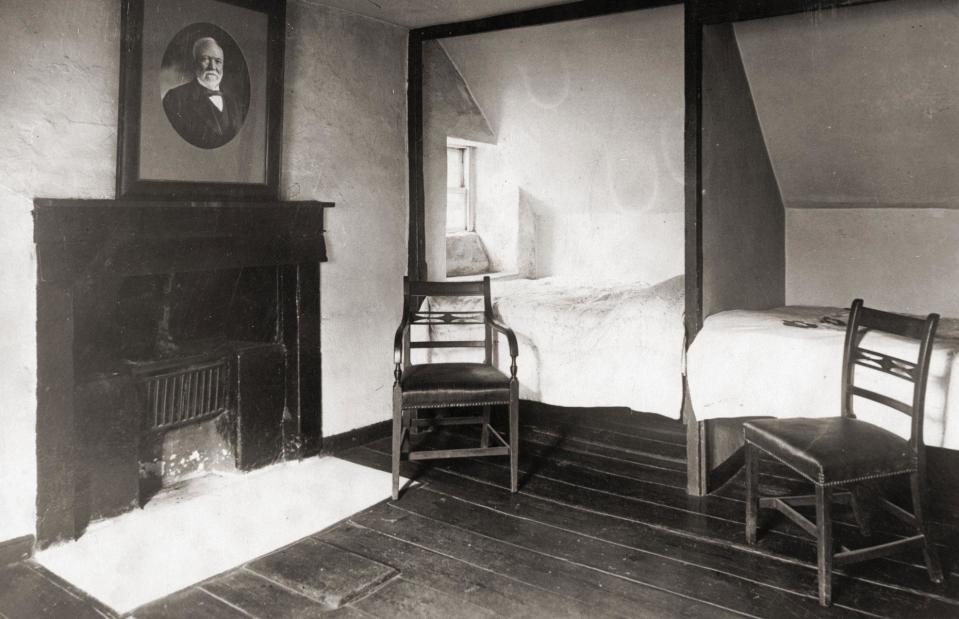

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Andrew Carnegie was born on 25 November 1835 in this modest two-storey cottage on Moodie Street in Dunfermline, Scotland.

He was the son of William, a handloom weaver of fine damask linen, and his wife, Margaret. Andrew was the eldest of their three children. His sister Ann was born in 1840 but sadly died in infancy, while his younger brother Thomas arrived in 1843.

Spartan accommodation

The Carnegies shared the first floor of the cramped cottage with another family and lived in one room (shown here in 1900). The ground floor of the property served as a weaving workshop. At the time of Andrew’s birth, his father’s weaving skills were in demand as the US had recently dropped all tariffs on linen products.

As a result, in 1836, William moved with his wife and son to a slightly larger house on Edgar Street and purchased several additional looms.

Harder times

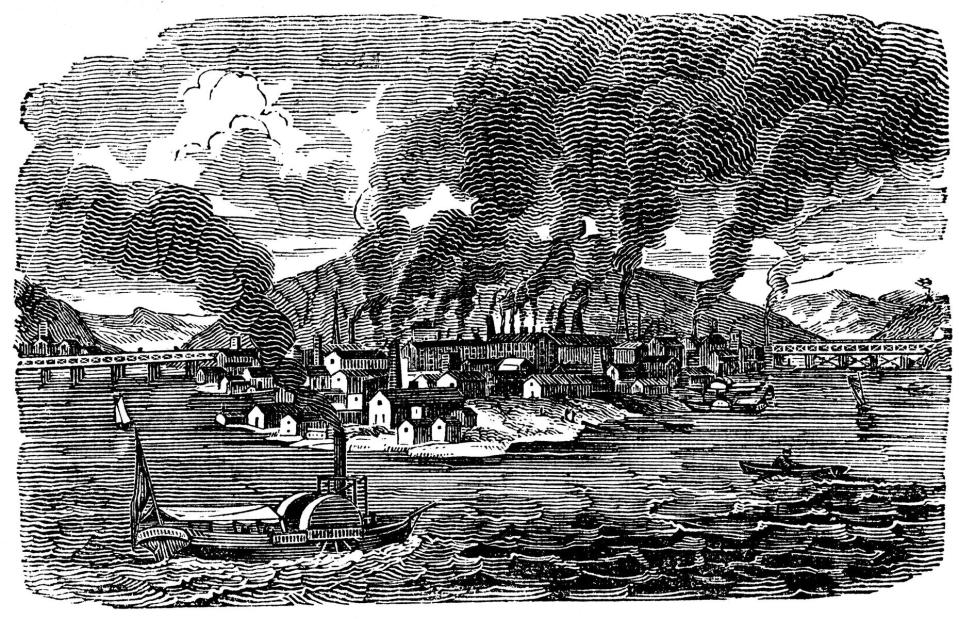

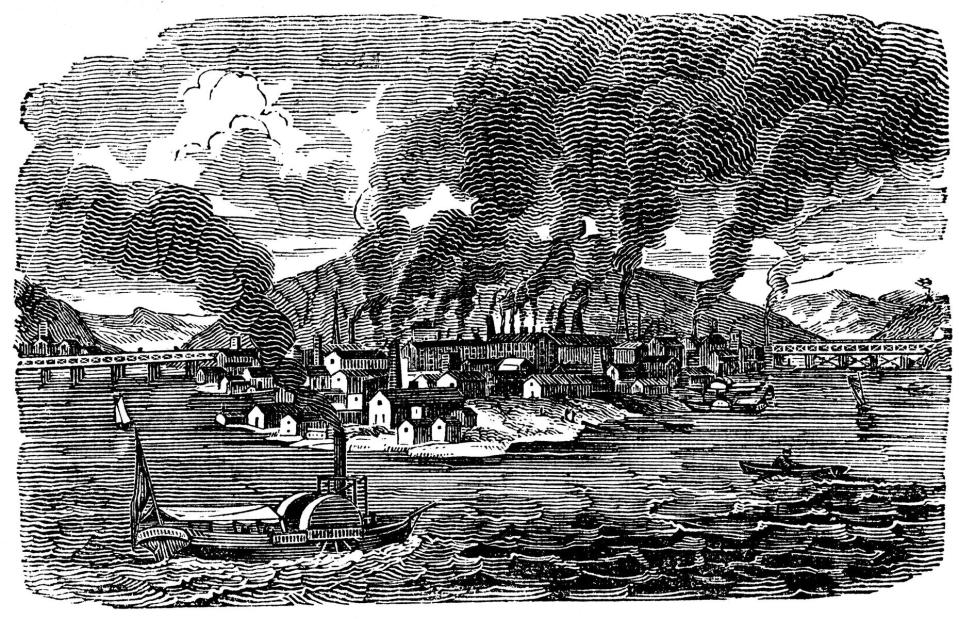

Print Collector/Print Collector/Getty Images

However, the family’s good financial fortune wasn’t to last. America’s Panic of 1837 and subsequent reimposition of tariffs led to decreased US demand for fine Scottish linens. Also, with the Industrial Revolution gaining pace, factories producing linen using steam looms began to massively undercut Scotland’s hand weavers.

The Carnegie family soon found themselves in dire economic straits. In the early 1840s, they were forced to move back into another tiny cottage on Moodie Street.

Entrepreneurial mother

![<p>Unknown photographer/Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/c_d_OkDv3wcNXbfT_4C.YA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/lovemoney_uk_264/7a77211024d61f6005946628ff699bc8)

![<p>Unknown photographer/Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/c_d_OkDv3wcNXbfT_4C.YA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/lovemoney_uk_264/7a77211024d61f6005946628ff699bc8)

Unknown photographer/Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]

While William lacked natural business savvy, resourceful Margaret was a born entrepreneur, a virtue that she clearly passed down to her eldest son. To make ends meet, she turned to selling confectionery, vegetables, and potted pies in her makeshift “sweetie shop”, which she operated out of the family home.

She also started cobbling shoes, a skill her shoemaker father had taught her, and ended up becoming the clan’s main breadwinner.

Young entrepreneur

Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

Andrew Carnegie’s entrepreneurial skills were evident from an early age. For instance, he cleverly funded his hobby of keeping rabbits and pigeons by naming each animal after his playmates, who fed them in return. By the age of 10, he was also keeping accounts for his mother’s grocery shop and selling gooseberries on the side.

Carnegie received little formal education and attended his local school for just a few years. Despite this, the future tycoon developed decent arithmetic and literacy skills – and it didn’t end there. Helped along by his maternal uncle, the political activist George Lauder Sr., he also acquired a lifelong love of books and developed enviable memory skills.

Chartist family

Like Lauder, Carnegie’s father and his maternal grandfather, Thomas Morrison, became involved in the Chartist movement, which sought to improve working conditions and political representation for Britain’s poor.

The rapid decline of the movement in the late 1840s, coupled with the Carnegies’ grinding poverty – they often went to bed early “to forget the misery of hunger”, according to Andrew – prompted William and Margaret’s difficult decision to emigrate with their two sons to the US.

Arrival in the US

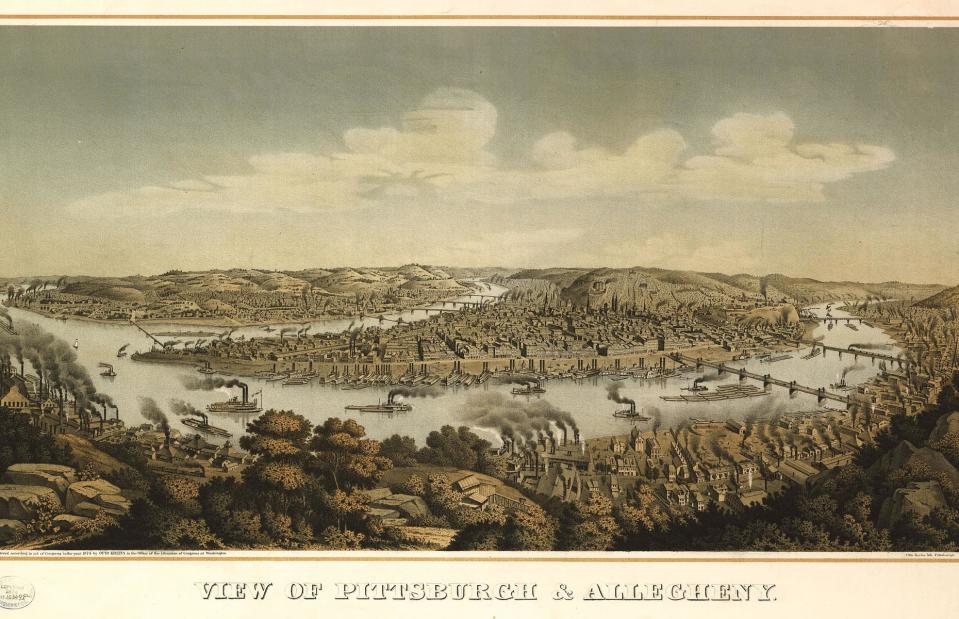

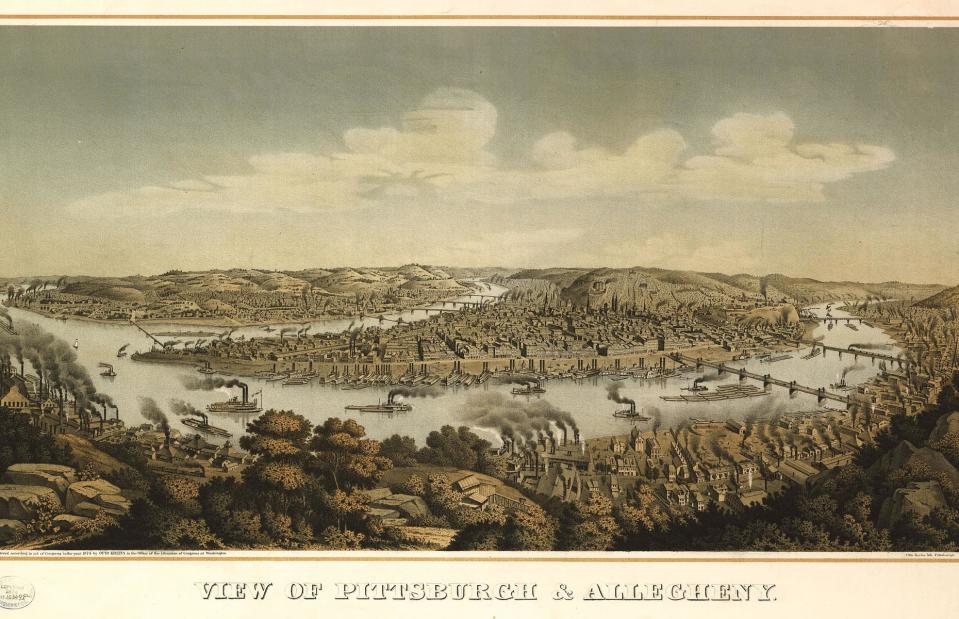

After struggling through the winter of 1847-1848, the couple sold their belongings and last remaining loom, and borrowed what they could to scrape together the money to pay for passage to America. Once they had arrived in the USA, they planned to join Margaret’s twin sisters, Annie and Kittie, who were living in Allegheny, Pennsylvania.

The family set sail on 19 May 1848 on board the former whaling ship Wiscasset. It would take them 50 days to reach New York. After arriving in the Big Apple, they travelled to Allegheny by coach, canal, railcar, and steamboat, a journey that ultimately took them three weeks. They settled in two rooms above a local weaver’s shop and William did his best to support his wife and two sons by weaving tablecloths, which he sold from door to door.

First job

Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images

However, his business was a total flop. Once again, it was Margaret who managed to keep the family afloat, earning around $4 a week ($155/£117 in today’s money) by cobbling shoes.

Andrew landed a job as a bobbin boy in the Scottish-owned Anchor Cotton Mills in Pittsburgh and worked exhausting 12-hour days, six days a week. He made just $1.20 a week.

Perilous work

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

William worked alongside his son at the mill for a short time but eventually left to return to his loom, putting further financial pressure on the family.

Luckily, the young Carnegie caught the attention of Scottish bobbin manufacturer John Hay, who hired him to tend the steam engine and fire the boiler in his factory, paying the teenager $2 a week, or around $78 (£59) in 2024 money.

But the work was grim and dangerous, and Carnegie revealed in later life that he often had nightmares about the boiler exploding.

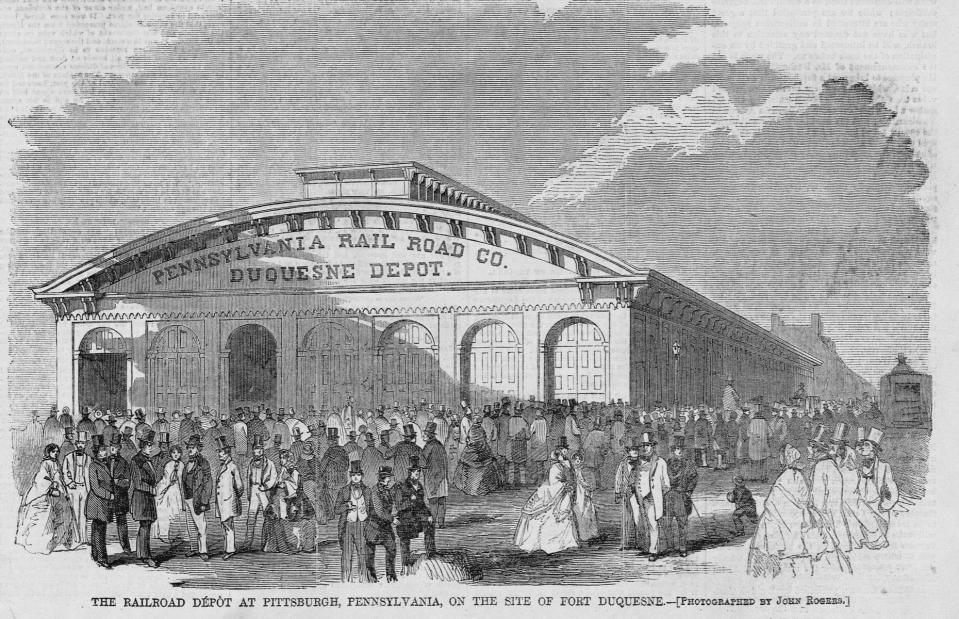

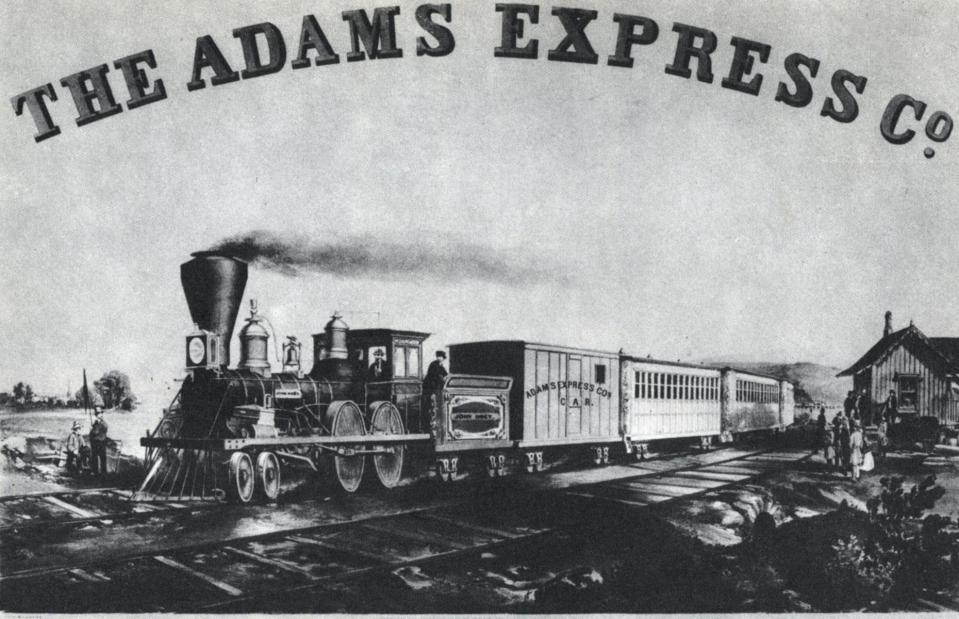

Messenger role

![<p>Library of Congress [Public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/32N5Capgcmqu6yVwvQm8zw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/lovemoney_uk_264/84383ea7a4072d774a9f3b36a81a8e9e)

![<p>Library of Congress [Public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/32N5Capgcmqu6yVwvQm8zw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/lovemoney_uk_264/84383ea7a4072d774a9f3b36a81a8e9e)

Library of Congress [Public domain]

A year later, Carnegie landed a job as a messenger boy for the O’Reilly Telegraph Company, an opportunity that made him “wild with delight” and, to paraphrase a quote from his autobiography, “lifted him into paradise”.

Earning $2.50 a week ($100/£76 today), he used his impressive memory skills to master the locations of Pittsburgh’s most important businesses and made many connections that would prove useful later on in his career.

Plum promotion

Carnegie also became one of the first people in America who could decipher telegraph messages by ear and, in June 1851, was promoted to a substitute operator role. He earned $4 a week, echoing his mother’s earnings.

Ever eager to improve his knowledge, the go-getting youngster made up for his lack of formal education by regularly attending the Free Library of Colonel James Anderson (pictured), where he taught himself a wide range of subjects.

Main breadwinner

![<p>Project Gutenberg [Public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/mWWG96ycKK18wA5t2tp2.A--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/lovemoney_uk_264/8aa4fdc9fb966a5ca248a1041bdd4609)

![<p>Project Gutenberg [Public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/mWWG96ycKK18wA5t2tp2.A--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/lovemoney_uk_264/8aa4fdc9fb966a5ca248a1041bdd4609)

Project Gutenberg [Public domain]

In 1852, Carnegie became an assistant operator earning $5.77 a week (around $230/£174 today), which made him the family’s main breadwinner. By the age of 16, he had been promoted to full-time operator.

By this point, thanks to his role and knack for forging connections, Carnegie was well-known among many of Pittsburgh’s most prominent figures.

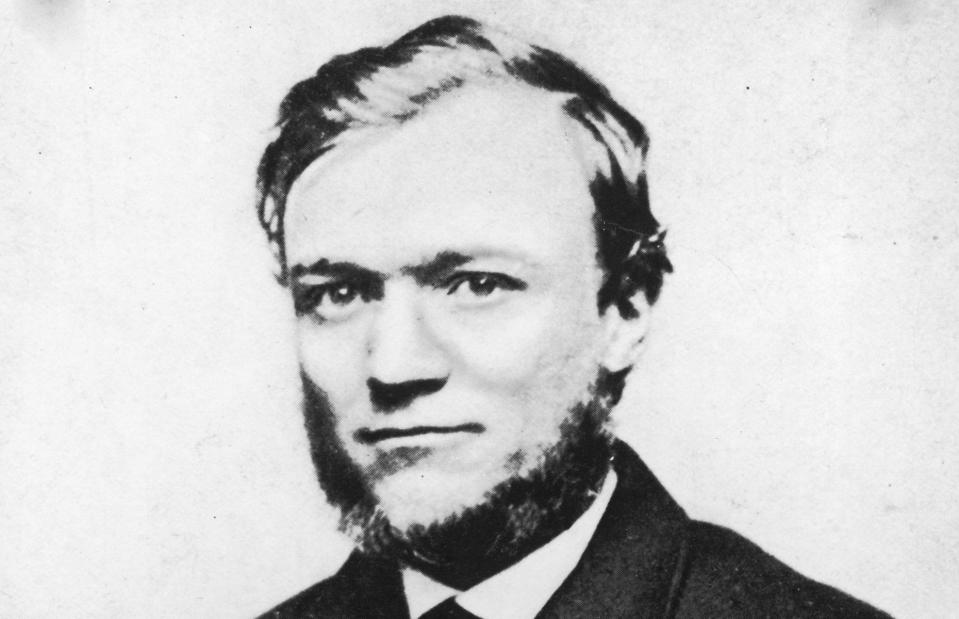

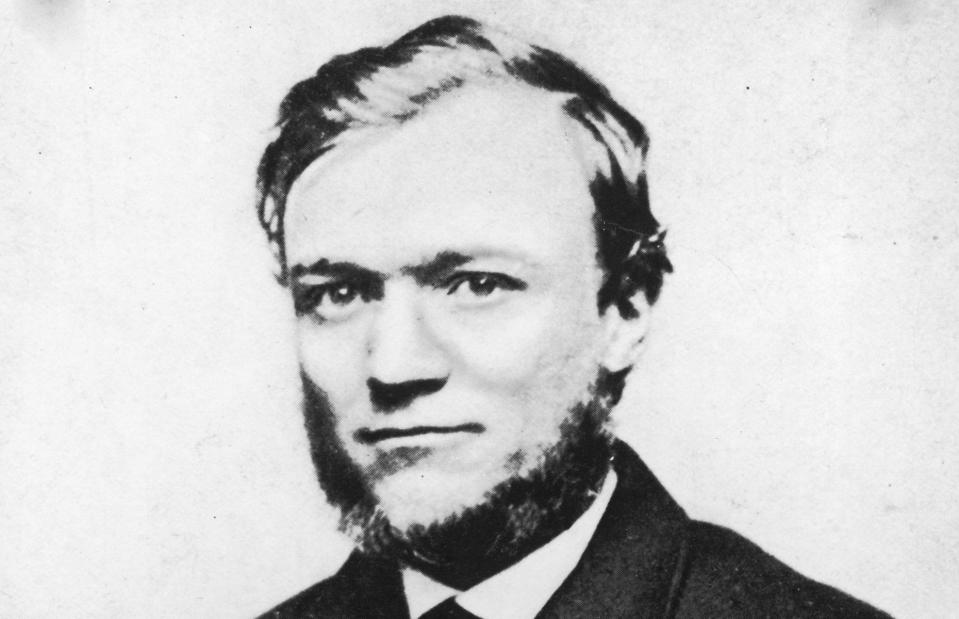

Big break

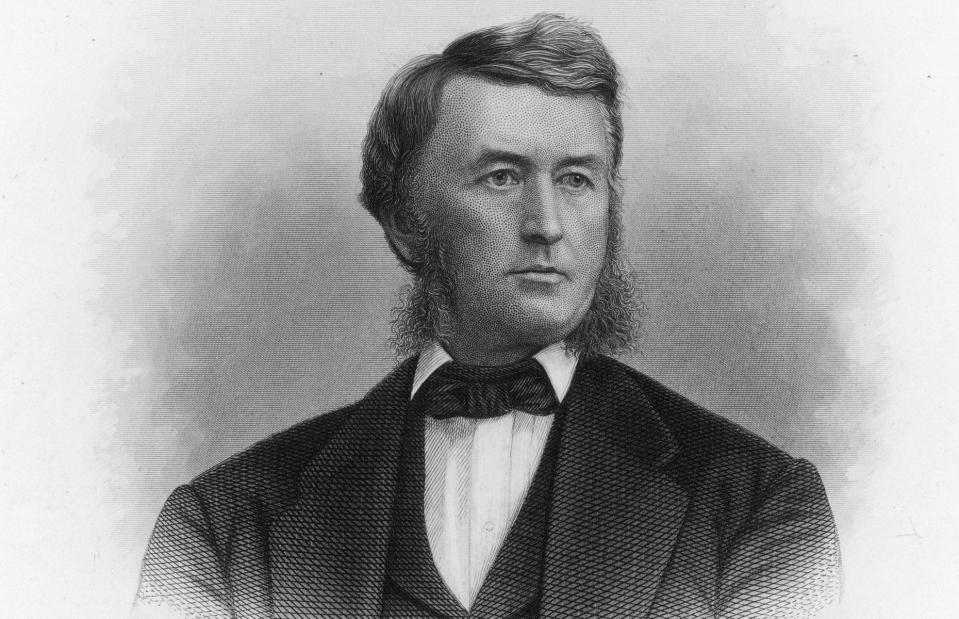

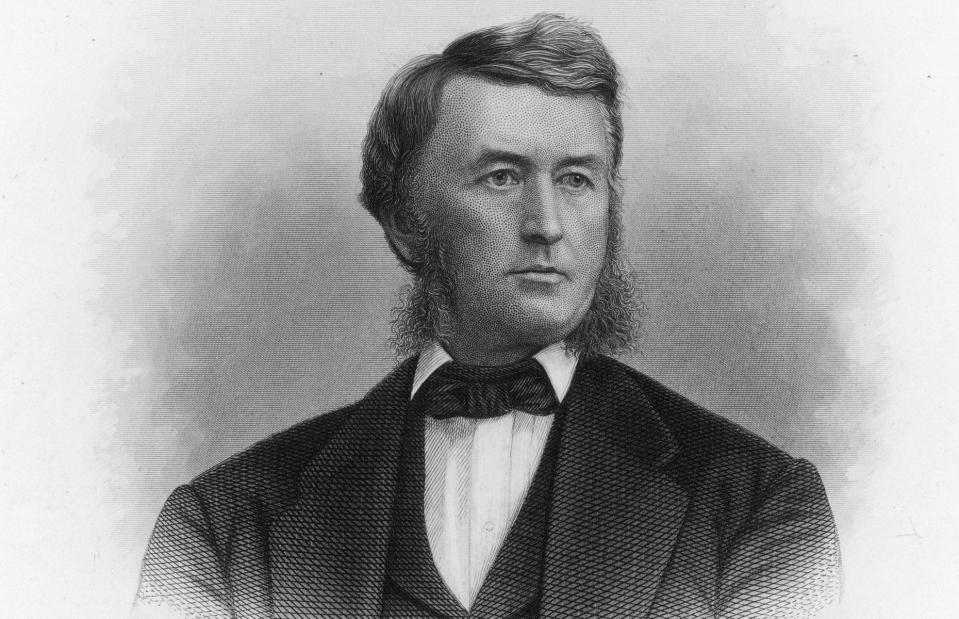

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Not long after the promotion, Carnegie bagged his real big break, securing a job that would put him on course to become the richest person in the world.

Thomas A. Scott (pictured), the new general superintendent of the burgeoning Pennsylvania Railroad Company, was looking for a private secretary and telegraph operator who could help him monitor rail traffic. He knew exactly who to hire, having already entrusted many an important message to the bright Carnegie.

Railroad job

CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

Carnegie started at the Pennsylvania Railroad Company on 1 February 1853 at the age of 17, pulling in a salary of $8.08 a week, the equivalent of $325 (£245) today.

But it wasn’t all good news. In 1855, the Carnegie family was rocked by tragedy when William passed away aged 51. His untimely death gave Andrew, who was 19 at the time, even more of a desire to succeed in order to support his mother and younger brother.

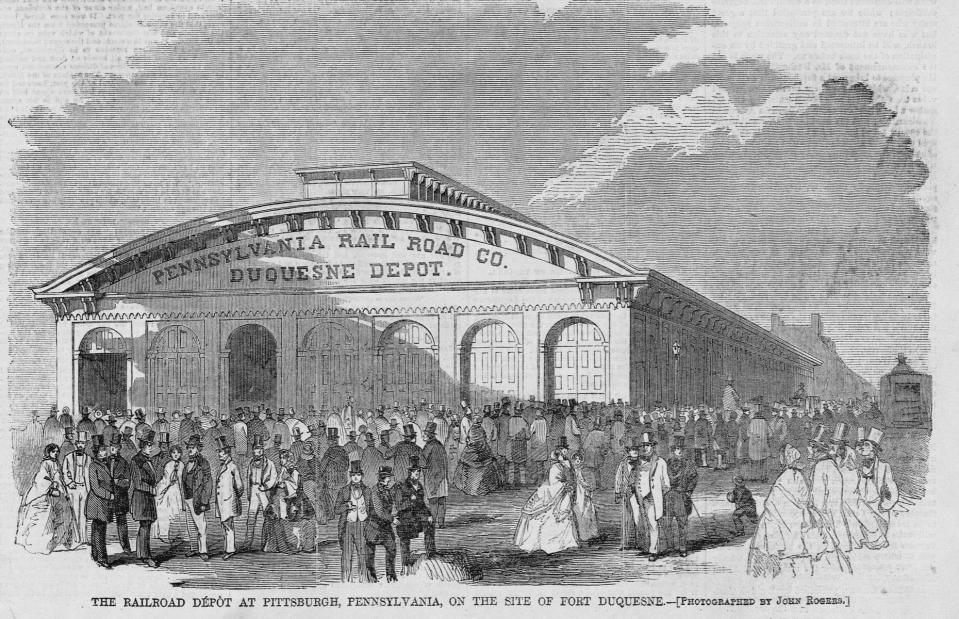

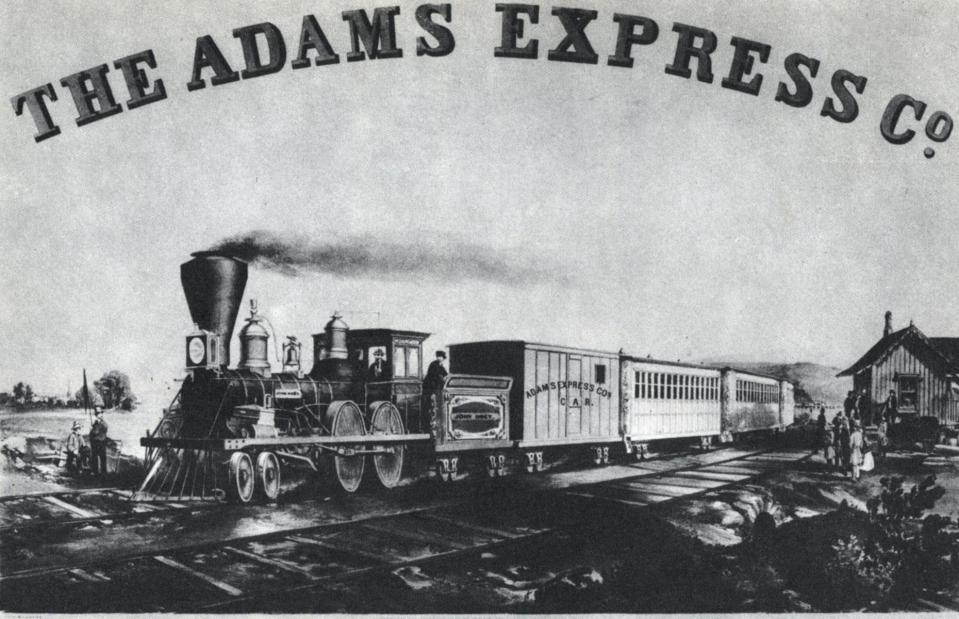

First investment

The Print Collector/Print Collector/Getty Images

Carnegie proved to be a model employee, wowing his boss with his skills and acumen. Scott, in turn, did much to nurture his protégé. In fact, Scott even initiated Carnegie’s first investment when he tipped him off in 1856 about the upcoming sale of 10 shares in the Adams Express investment company. Carnegie persuaded his mother to mortgage the family home and snapped up the stock for $500, around $18,000 (£14k) in 2024 money.

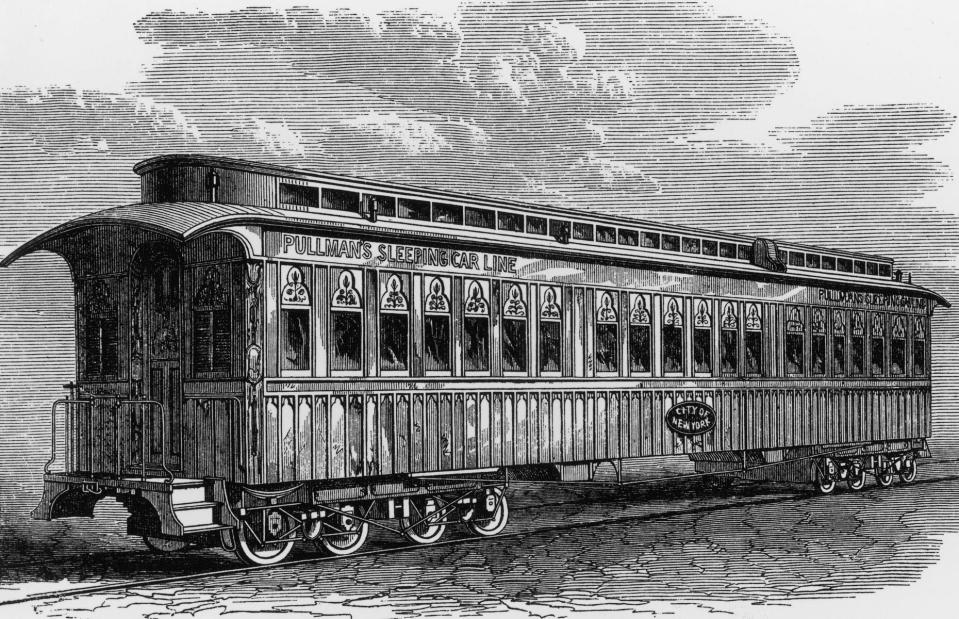

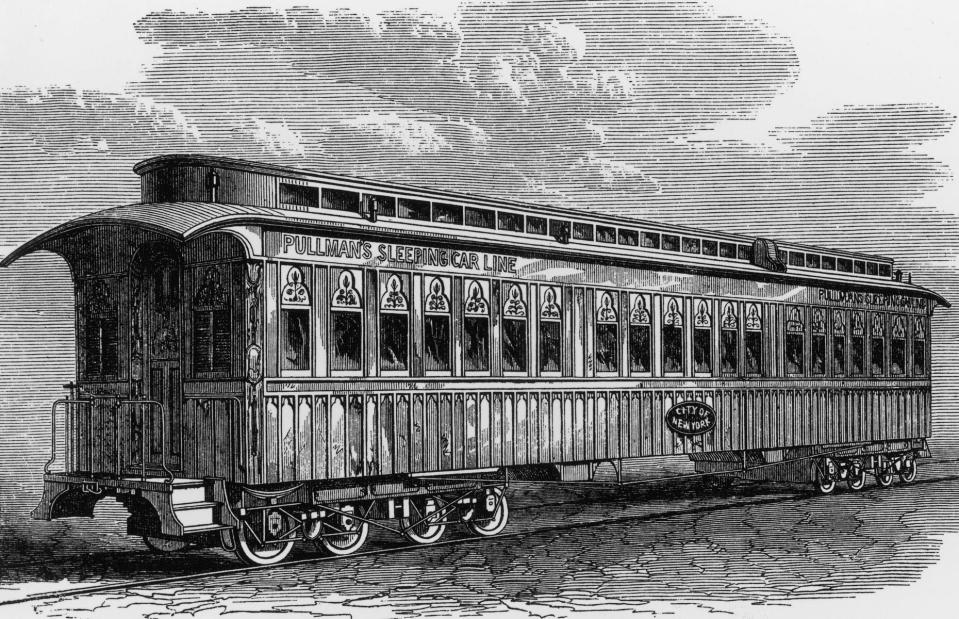

With the railroad industry booming, the dividends began flowing in. In addition, in 1858, Scott ensured that a one-eighth interest in a company making sleeper cars was earmarked for Carnegie, who took out a bank loan of $1,250, or $47,000 (£36k) in today’s money, to finance the acquisition. Reinvesting his returns, Carnegie also made several other lucrative investments around this time.

Superintendent position

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

In 1859, Scott, who had risen to become the Pennsylvania Railroad Company’s vice president, offered Carnegie the position of superintendent of the Western Division. Andrew duly accepted and received an annual salary of $1,500, or $56,000 (£42k) today.

Carnegie was able to further support his family by offering them jobs. He hired his 16-year-old brother Thomas as his personal assistant and also arranged a role for his cousin Maria Hogan, who became America’s first female telegraph operator.

Dividend income

By 1860, Carnegie had repaid the bank loan using the dividends he’d received, and his investment in the sleeping cars company was netting him just over $5,000 a year. That’s a sizable $186,000 (£140k) in today’s money.

Around this time, he arranged the merger of the sleeping cars business with George Pullman’s company, which proved to be extremely lucrative for the young entrepreneur.

Civil War

CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

The American Civil War broke out in 1861. Carnegie was transferred to the War Department and charged with organising the Military Telegraph Service and transporting supplies by rail to Union forces.

Over the next few years, he devoted himself to his wartime role, bar a stint in 1862 that saw him take three months of leave due to stress. He returned briefly to Dunfermline with his mother, recalling in his autobiography that “I seemed to be in a dream… I felt as if I could throw myself upon the sacred soil [of home] and kiss it”.

During this period, he continued to make profitable investments, including in the steel and oil industries.

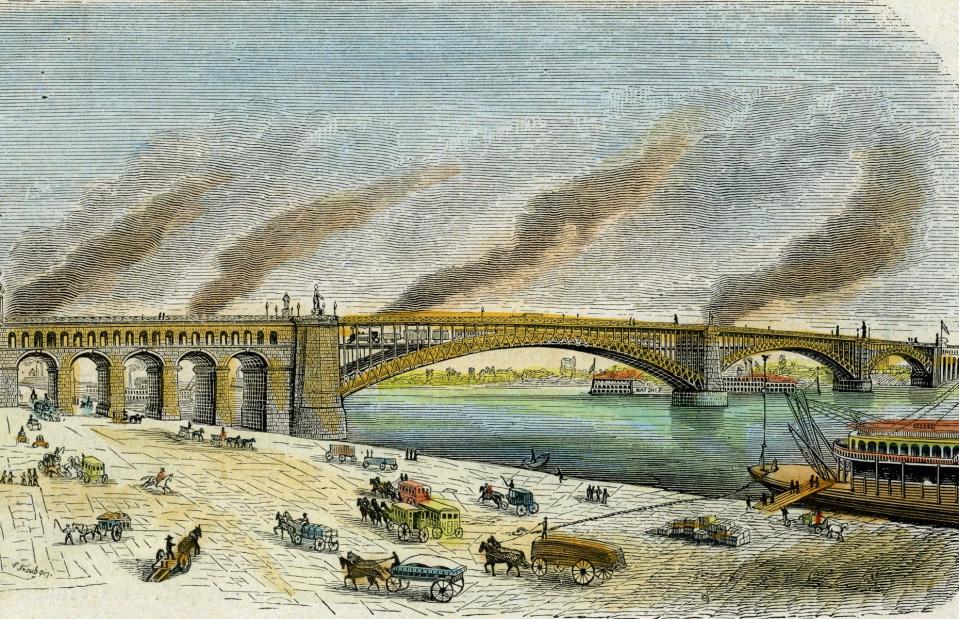

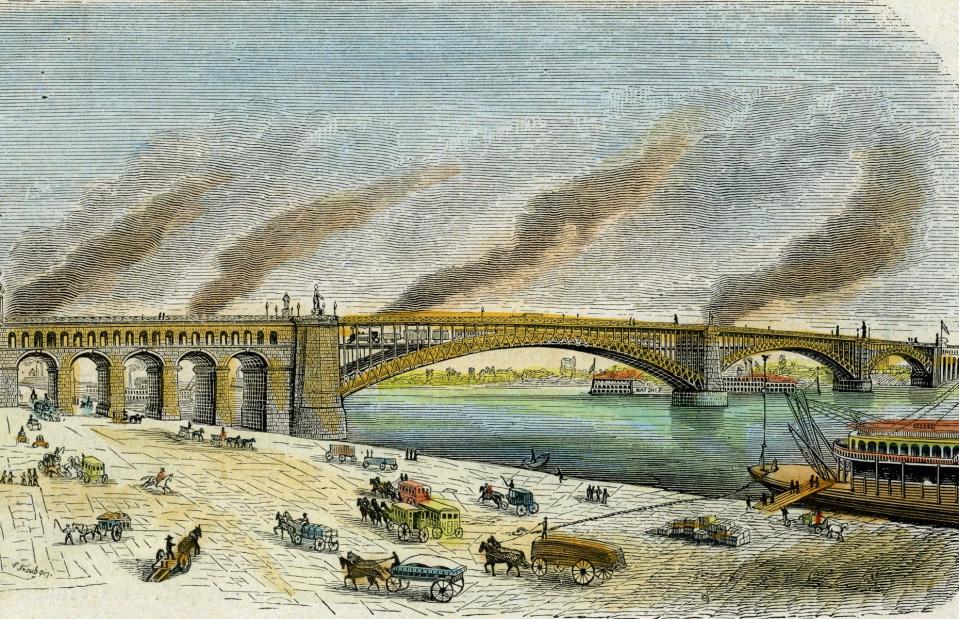

Business move

The Print Collector/Print Collector/Getty Images

Following the end of the Civil War in April 1865, Carnegie resigned from the Pennsylvania Railroad Company to focus on his career as an investor. He also left to head up his newly-formed ironworks business, Keystone Bridge Company, which is perhaps best known for building the Eads Bridge in St Louis.

By this time, Carnegie had moved to New York with his mother. In 1868, while staying in the city’s fashionable St Nicholas Hotel, he wrote a pledge to give away the surplus of his wealth to worthy causes.

Cashing in

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

By his early 30s, Carnegie was positively raking it in, having invested in everything from railroads and ironworks to steam boats and oil wells. His various business ventures were now making him around $50,000 a year, a staggering $947,000 (£715k) in today’s money.

Despite this, he decided to “put all [his] good eggs in one basket” and focus on the iron industry. He formed a series of ironworks, which made huge sums of money by supplying the metal for railroads, bridges, and other infrastructure projects. But it was a visit to London in 1872 that would get the ball rolling and allow Carnegie to make the really big bucks.

Bessemer process

![<p>Thomas Oldham Barlow/Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 4.0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/BvcZsvyP.B76lByd6P8VKw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/lovemoney_uk_264/30df25ca723ceca8fc689175d8549570)

![<p>Thomas Oldham Barlow/Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 4.0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/BvcZsvyP.B76lByd6P8VKw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/lovemoney_uk_264/30df25ca723ceca8fc689175d8549570)

Thomas Oldham Barlow/Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 4.0]

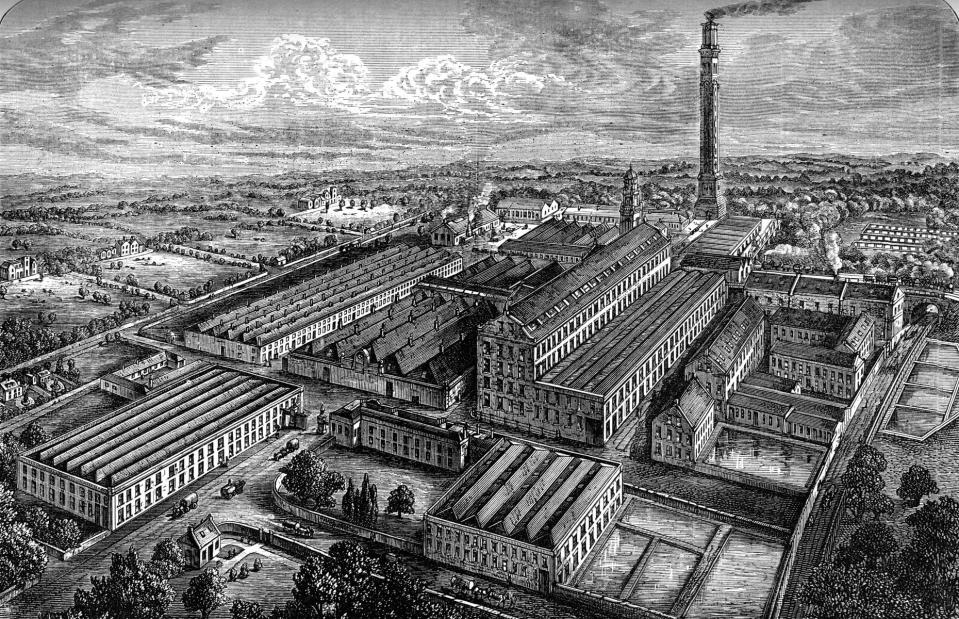

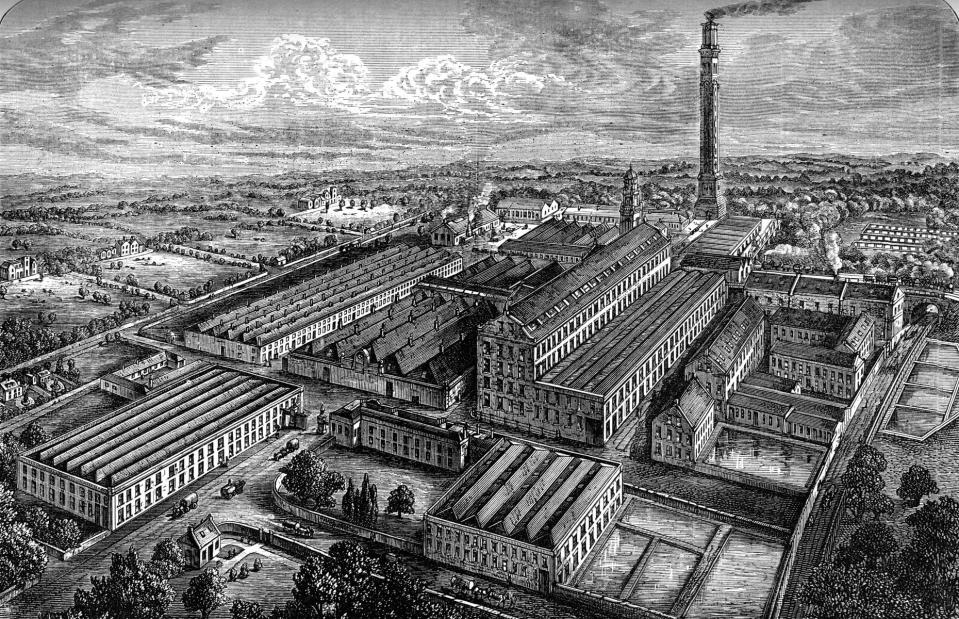

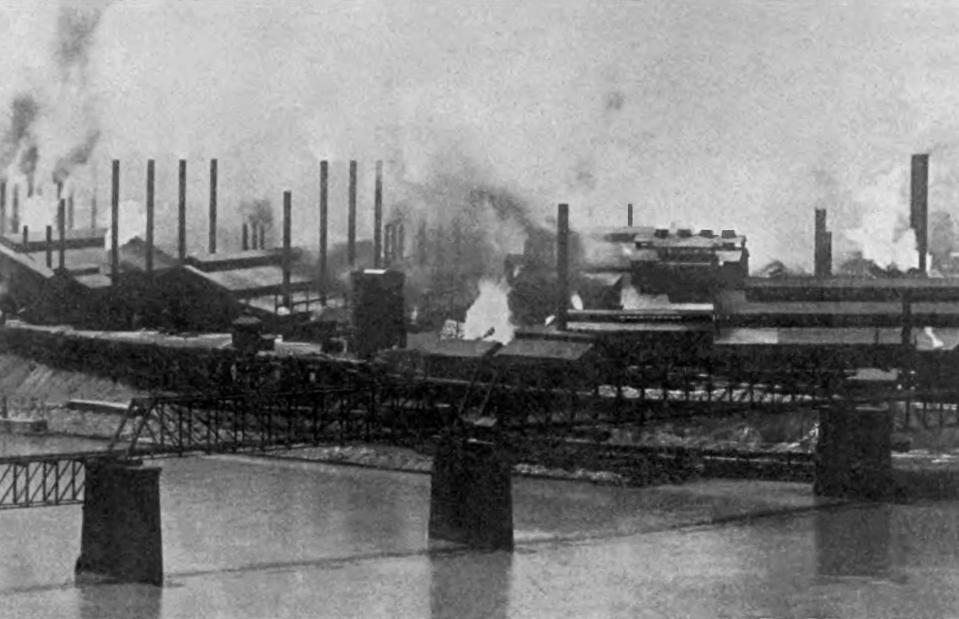

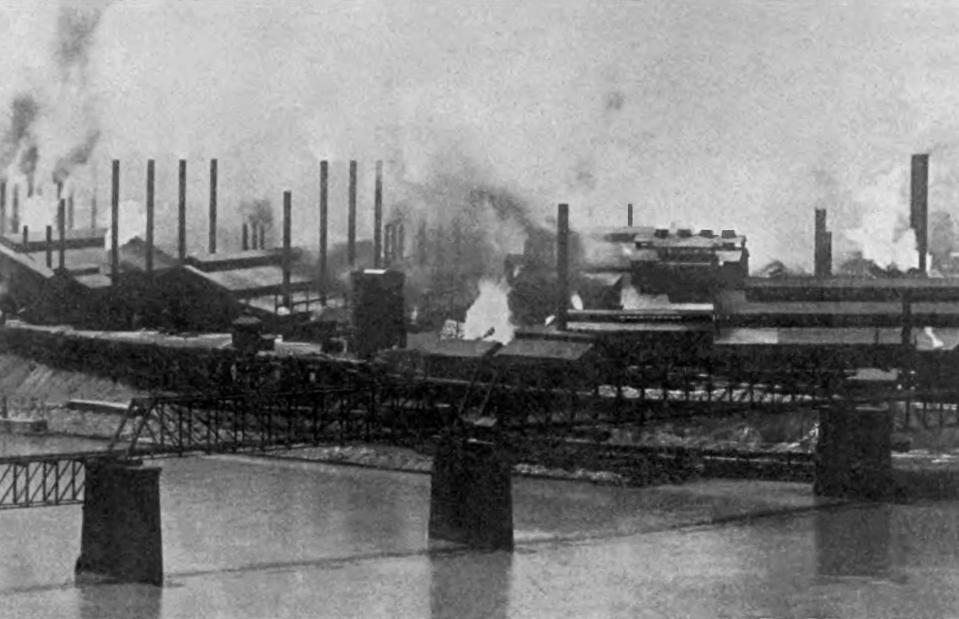

During his trip, Carnegie met Henry Bessemer, who had developed a process to mass-produce steel cheaply. Recognising that steel, rather than iron, was the future, he formed the steel rail business Carnegie, McCandless & Company in 1873, opening the firm’s first steel mill the following year.

During the latter half of the 1870s, Carnegie took advantage of the economic slump to snap up competing mills and suppliers of the raw materials essential for making steel and pioneered horizontal and vertical integration. Thanks to its highly efficient management system, his business was able to price out any remaining competitors. By 1878, Carnegie’s firm was valued at $1.25 million ($39m/£29m today). He owned just under two-thirds (59%) of the shares in the company.

Business acumen

![<p>Project Gutenberg [Public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/8JsNWyAigX1SgiVGj6nfeA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/lovemoney_uk_264/a2b927ff602335c69173dbaac8222f89)

![<p>Project Gutenberg [Public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/8JsNWyAigX1SgiVGj6nfeA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/lovemoney_uk_264/a2b927ff602335c69173dbaac8222f89)

Project Gutenberg [Public domain]

In 1881, Carnegie placed industrialist Henry Clay Frick in charge of his company’s operations and obtained a controlling stake in Frick’s coke empire.

Two years later, the Scottish-born magnate acquired his firm’s biggest competitor, Homestead Steel Works, cementing his control of the burgeoning American steel industry.

1887 wedding

![<p>Unknown photographer/Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/JuMOnFIUkc8d8vFz17RumA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/lovemoney_uk_264/c4703b14b4fa7c49bfcacc837c1fe6b7)

![<p>Unknown photographer/Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/JuMOnFIUkc8d8vFz17RumA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/lovemoney_uk_264/c4703b14b4fa7c49bfcacc837c1fe6b7)

Unknown photographer/Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]

Tragedy struck in 1886 when Carnegie’s beloved mother, Margaret, and brother, Thomas, died within weeks of each other.

The following year, the tycoon, who was allegedly so devoted to his mother that he refused to marry while she was alive, tied the knot with Louise Whitfield (pictured). Carnegie’s bride signed a prenup that affirmed her new husband’s commitment to give away the lion’s share of his money during his lifetime.

The Gospel of Wealth

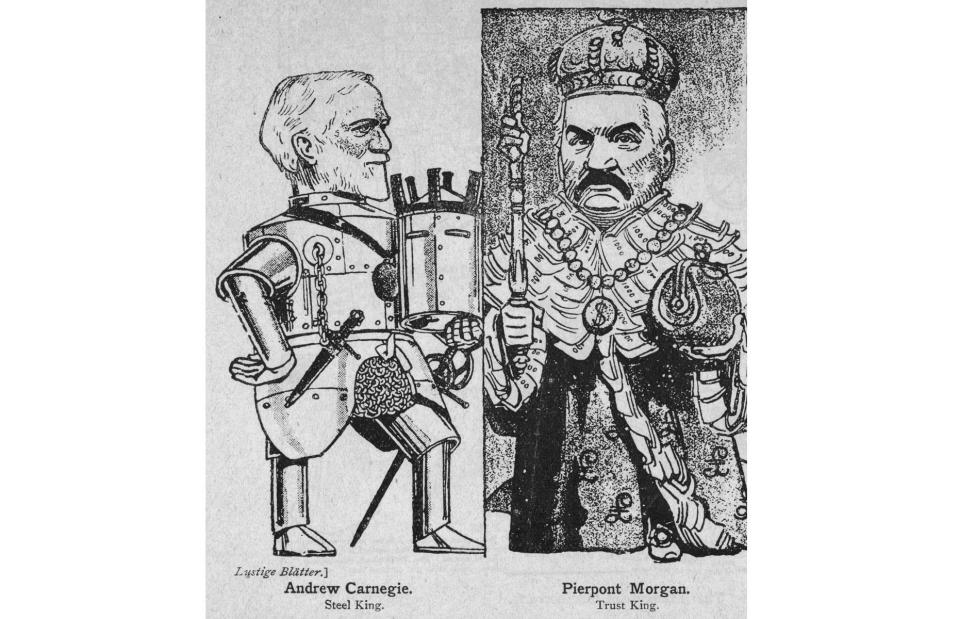

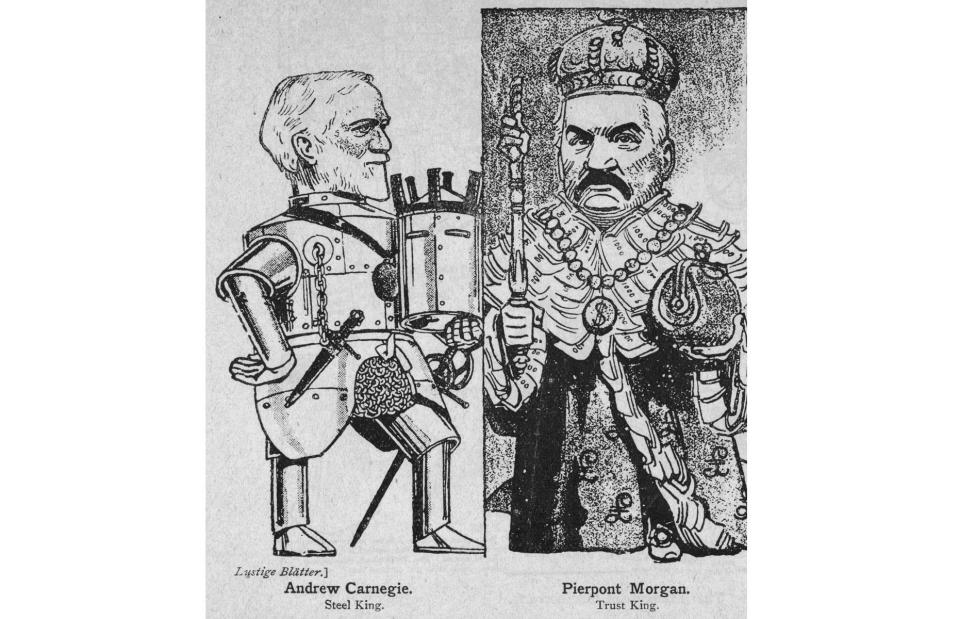

Archive Pics/Alamy Stock Photo

By 1889, steel production in America had surpassed that of the UK, and since Carnegie controlled most of it, he’d become one of the richest people in the country.

Later that year, the philanthropic industrialist wrote The Gospel of Wealth, an article that argued that the rich should give away most of their money for the good of society. This, along with Carnegie’s support for trade unions and workers’ rights, which he famously advocated for in an 1886 article, won him global praise.

Damaged image

Alpha Stock/Alamy Stock Photo

However, Carnegie’s glowing reputation was tarnished in 1892, the year he formed Carnegie Steel. The trouble began when a strike at the Homestead Steel Works was brutally crushed after 143 days by his staunchly anti-union head of operations, Henry Clay Frick.

This resulted in the deaths of 12 people, and even though Carnegie was in Scotland at the time and wasn’t directly involved, many ultimately blamed him for the violence.

New daughter and homes

![<p>Internet Archive Book Images/Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/a6ff1eBfnhAbB9qUmRbPag--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/lovemoney_uk_264/f0a711f1d9d11b562adfd2bca348068a)

![<p>Internet Archive Book Images/Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/a6ff1eBfnhAbB9qUmRbPag--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/lovemoney_uk_264/f0a711f1d9d11b562adfd2bca348068a)

Internet Archive Book Images/Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]

In 1897, Carnegie and his wife Louise welcomed their only child, a daughter called Margaret who was named, of course, after the mogul’s mother.

The following year, the industrialist bought Skibo Castle in the Scottish Highlands and went on to spend millions on its renovation. He also commissioned the construction of a handsome mansion in Manhattan, completed in 1902, which is now used as the Cooper-Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

Bumper sale

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

In 1901, Carnegie sold his eponymous steel business to financier J. P. Morgan for $480 million, or $17.4 billion (£13.1bn) in today’s money.

According to the Carnegie Corporation of New York, his peak net worth amounted to the modern-day equivalent of $375 billion (£283bn), which would have easily made him the richest person on the planet, although John D. Rockefeller ultimately eclipsed him.

The company was eventually merged with other steel firms to become US Steel.

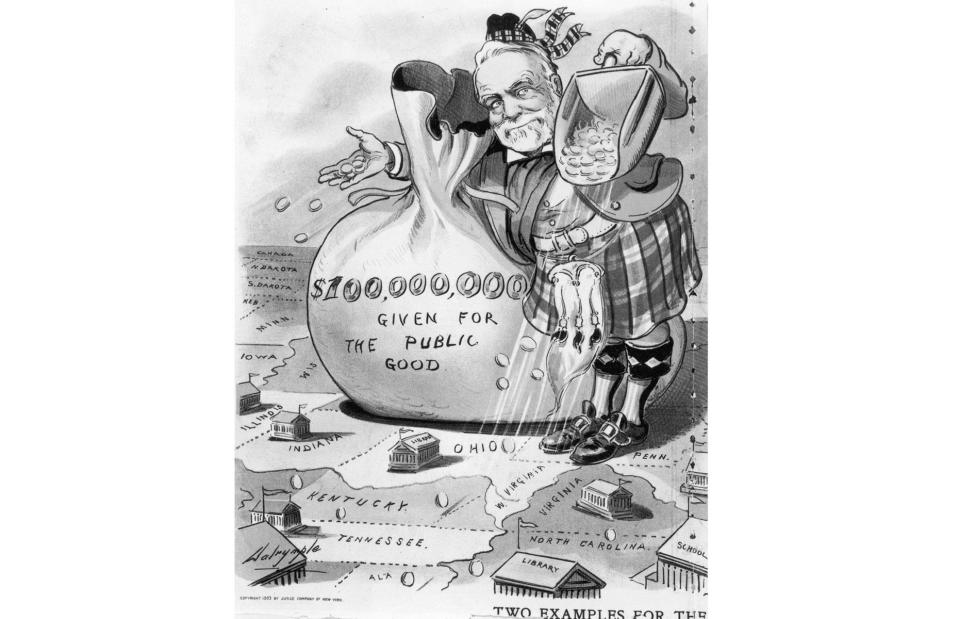

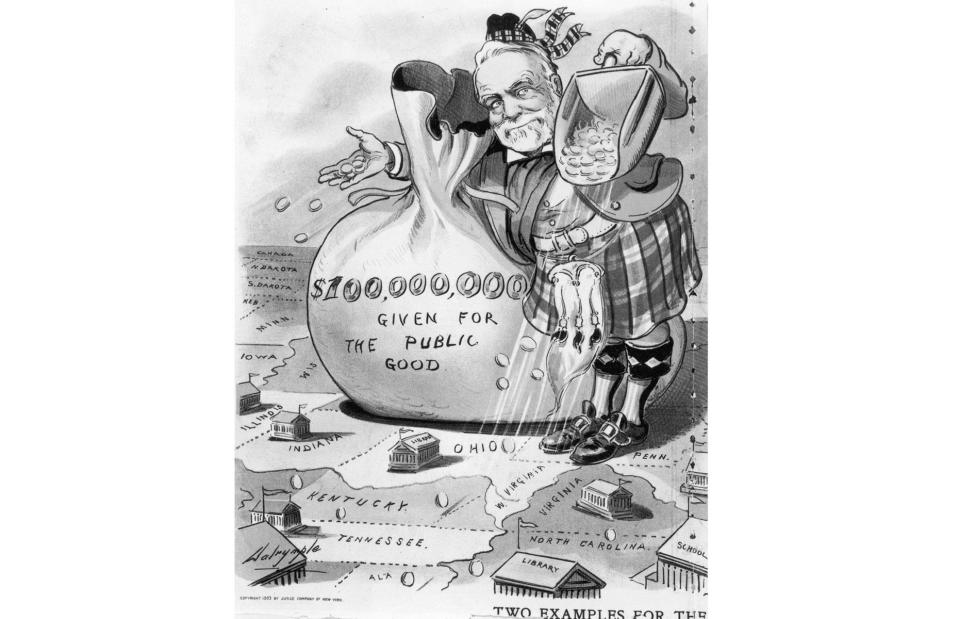

Charitable giving

Following the sale, Carnegie retired from business, devoting himself entirely to giving away his enormous fortune. His philanthropy tended to focus mainly on promoting education and world peace.

In total, he funded a whopping 2,509 libraries worldwide and bankrolled numerous institutions that bear his name, including the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh, the Carnegie Mellon University, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, and the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Learning.

Carnegie Corporation

National Film Board of Canada/Library and Archives Canada

And it doesn’t end there. Thanks to the ongoing work of the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the charitable foundation that Carnegie founded in 1911, the industrialist’s generosity has lasted well past his lifetime. The organisation has provided funding for everything from the development of insulin and the dismantling of nuclear warheads to the creation of Sesame Street.

In March 2022, more than a century after Carnegie’s death, the foundation announced that it was donating $1 million (£755k) to the International Rescue Committee to support Ukrainians who were being forced to flee their homes due to the Russian invasion.

Remarkable legacy

Marceau/Underwood Archives/Getty

By the time he passed away in August 1919 at the ripe old age of 83, Carnegie had given away the vast majority of his wealth. He’d endowed the remaining $135 million, which equates to $2.4 billion (£1.8bn) today, with the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Often considered one of the world’s greatest philanthropists, Carnegie is renowned for stating that “the man who dies thus rich dies disgraced”. He certainly stuck by his famous motto.

Now discover the incredible story of ‘the richest girl in the world’