Bussiness

Can anything stop another Scottish summer of discontent?

PA Media

PA MediaPay pressures are rising to become one of the biggest early challenges the UK government faces, and they are building up more conspicuously for the Scottish government.

Instead of the time-worn ‘Winter of Discontent’ headlines, the disputes are on course to become a problem for the public long before then – as soon as this glorious and possibly quite smelly summer, if strikes stop bin collections.

In addition to council workers, which could extend to Scottish schools as the new term starts, there are strike ballots under way by rail unions at ScotRail, with a drivers’ work-to-rule already biting into the timetable.

Then, there’s the staff who work on Edinburgh’s tram line currently voting on action to get more time for toilet breaks.

In Whitehall, Labour ministers have inherited strikes, including two years of unresolved confrontation with Aslef train drivers, which affect most operators including cross-border trains.

Junior doctors in the English NHS have been through 11 rounds of strikes in pursuit of their claim for a 35% pay increase to make up lost ground in real terms earnings.

Ministers entering office in Whitehall have also fallen heir to some big bills implied in the findings of the independent public sector pay review bodies.

Published annually, some of these cross the border into Scotland – senior NHS doctors and dentists, the armed forces, officials in Whitehall departments, Scottish government senior civil servants and judges.

Honeymoon period

Where the pay review recommendations do not apply in Scotland – most civil servants, local government workers, teachers, junior doctors, quango staff and government-owned companies – they still influence pay negotiations.

These pay reviews are still to be published for this year, but they were leaked last week, suggesting an average 5.5% pay increase recommended.

While well ahead of current price inflation, that is close to the most recent increase in average weekly pay, for March to May. However, that pay inflation figure is on a downward trend (still increasing, but by smaller percentages).

The new Chancellor, Rachel Reeves, has acknowledged that the Labour government may have to accept those recommendations.

PA Media

PA MediaNot only is that the norm, and the least Labour’s union affiliates would expect, but she cited the threat of strike action as one of the considerations she is balancing up.

Pay review bodies are also required to take account of recruitment and retention challenges, which are a big problem for many public services.

Having chosen to inherit also the fiscal constraints of her Tory predecessor, that pay will have to be at the expense of either jobs or a big efficiency drive, to get public sector workers increasing their productivity.

Ms Reeves can hope for something of a honeymoon period where the Labour election mandate cuts her some slack with public sector unions, or at least buys some time.

Not so for the Scottish government. It faces a daunting range of pay disputes in the public sector, from local government to railways. And it does not have the advantage of a fresh mandate.

It struck a two-year, 14.5% deal with junior doctors in May last year, and Holyrood ministers boasted since then that they avoided England’s strikes.

But that risked increasing demand for similar increases for other workers, as did last year’s 7% deal for police and prison officers, and there is diminishing budget headroom to continue that approach.

In many cases, the employer is not the Scottish government, but councils or companies effectively controlled by ministers.

PA Media

PA MediaThe fact that the Scottish government is the main source of funding puts the pressure on to ministers, directly or indirectly.

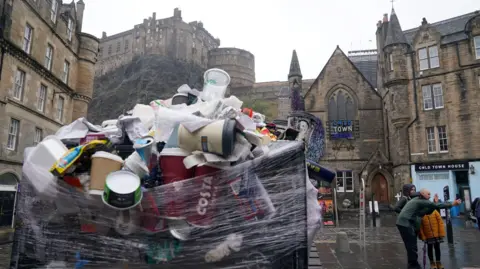

Local government unions have chosen to pick their fight in refuse collection and recycling. They found two years ago that it can have a quick impact if rubbish goes uncollected, especially when the temperature is up in summer and during the Edinburgh festivals.

So that’s where they are exerting pressure again. The councils say they cannot afford more than they have offered, and so both sides have agreed to take it to Scottish ministers, in pursuit of more money.

The plan is to issue strike dates next Wednesday, ahead of the first weekend of the capital’s busiest month.

Edinburgh’s bin collectors are taking the lead on this, while ballots in other council areas have returned results that would allow the bin collection strike to spread.

Where the legal threshold for strike action was not met, there is some re-balloting.

Lessons to learn

If the smell of rotting rubbish doesn’t waft up Calton Hill to St Andrew’s House with sufficient pungency, there are other pressure points that could follow in council services, including non-teaching staff in schools and early learning centres.

They were at the forefront of the council dispute last year, closing down schools with a knock-on effect on parents.

Last week, Unison started balloting its 39,000 members in schools, with a warning that strike action could start in September. The union has rejected an offer from Cosla, representing council employers, of 2.2% for six months from April and 2% for the following 12 months.

PA Media

PA MediaScottish teachers, negotiating separately and a big part of the council pay bill, stepped back from strike action last year, on the understanding there would be more for them this year.

This year’s pay, due to be settled by next week, has only gone one round of talks, and the two sides are a long way apart.

The other two big unions in councils, Unite and GMB, are able to co-ordinate action across the workforce.

Yet at the same time, there is a membership recruitment rivalry between unions which can make it more difficult to get to a settlement. They have an interest in out-toughing one another.

Work to rule

That rivalry also stokes up union activity on the railways.

ScotRail settled with Aslef drivers in the dispute which rumbles on across England and across the Border.

But this year sees another pay negotiation, and already there’s a work to rule. That means many drivers don’t turn up for weekend shifts, many of which are rostered on an overtime, ‘goodwill’ basis.

ScotRail responded by switching to a temporary, reduced timetable.

Aslef and the other unions, the RMT and TSSA, are now looking to use strike action, having rejected ScotRail’s offer of a 9% pay increase in six stages over three years.

For at least one of them, the RMT, that extends to Caledonian Sleepers, the overnight services also controlled by the Scottish government, with a ballot result due on August 8.

There are common themes here. Most strike action is aimed ultimately at governments. Strikes are less frequent in the private sector, where unions typically have a much lower membership share.

Where strikes threaten, private sector employers have more flexibility on pay, and can often find more flexibility on changed conditions to help cover the increased pay bills.

Threatened strikes by baggage handlers at Scotland’s airports have been averted that way, with deals worth 7.4% at Menzies contractor at Edinburgh Airport and up to 12.8% in Glasgow and Aberdeen for those in the ground handling firm ICTS.

By bringing railways into public control, as the Scottish government chose to do and the UK government intends to follow, the ability to pressure politicians can increase union leverage.

It could have been more effective in pressuring Scottish ministers if, as expected, the general election had been in autumn.

Behind all this is price inflation. With tight government finance while prices took off, public sector workers did not keep up with prices or with private sector pay. That catch-up is taking place now, for some, and it’s uneven. It’s those with the most workplace bargaining power who are the winners.