Bussiness

Alex Salmond obituary: A man and a politician of contradictions

PA Media

PA MediaAlex Salmond was a man and a politician of extreme contradictions.

A one-time radical firebrand, he moved his party from the political margins and perpetual opposition to government and the mainstream of Scottish public life.

He was a gambler and divider of opinions who became a rock-steady first minister with a mission to show voters that he could govern for all, using devolution to prove independence was nothing to be frightened of.

And he was a powerful communicator who would see his reputation diminished amid allegations of sexual misconduct, a criminal trial and exile from the SNP.

His death at the age of 69 brings to an end a remarkable life and political career and an important chapter in the story of the independence movement.

Salmond’s reputation as a political heavyweight ensured he was a high-profile politician across the UK long before he won Holyrood’s top job.

In a BBC Scotland profile in 2011, former Conservative cabinet member Michael Portillo described him as the only Scottish politician to become well known in England and internationally while spending most of his career in Scottish politics.

“I regard him as the outstanding politician not to have come out of Scotland, but to have remained in Scotland,” he said.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBorn on Hogmanay 1954 in Linlithgow, Alexander Elliot Anderson Salmond grew up in a town soaked in Scottish history and tradition.

A talented boy soprano, he sung in St Michael’s Parish Church. The 15th Century kirk, which stands next to Linlithgow Palace, was a place of royal worship and the site of Mary Queen of Scots’ baptism.

Salmond described his parents as working class nationalists with a small ‘n’. He was proud to have grown up in a council house, educated in Scotland’s distinctly egalitarian school system built on the Kirk’s traditions.

From there he made his way to the University of St Andrews, where he studied economics and medieval history and joined the SNP almost immediately after arriving there in 1973.

The party was just about to take off, achieving 30% of the vote and sending 11 MPs to Westminster in the election of October 1974.

A contemporary at St Andrews, future BBC Scotland political editor Brian Taylor, later remembered him as a “mischief maker” at St Andrews.

“If he had two options to make a political point, he would always use the one which allowed him to make mischief as well as making the point,” he said.

“But he was also a brilliantly focussed politician. He was president of the Federation of Nationalist Students, and he was very focussed. He was easily the same quality as his political contemporaries such as Gordon Brown down in Edinburgh.”

After university, the radical young political activist who wanted to bring about the end of the United Kingdom state then embarked on a career right at the heart of it.

In 1978, he entered the Government Economic Service (GES) as an assistant economist in the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries for Scotland, part of the now defunct Scottish Office.

After two years later he moved to the Royal Bank of Scotland, where he worked for seven years as an economist, eventually coming to specialise in oil and gas.

But all the while the world of politics was exerting its pull. An active member of the SNP, he played a prominent role in the party’s dissident 79 Group.

They wanted to move the SNP to the left, seeking the support of working-class and disaffected Labour voters who were unhappy at the failure of their party to deliver the promised Scottish Assembly.

The group was expelled from the party in 1982 but his colleagues saw Salmond as too talented to be left out in the cold and brought the trouble-makers back into the ranks.

By the late 1980s, as Thatcherism swept across Scotland and the country felt the full force of her economic policies on its industrial sector, Salmond was seen as a rising star and potential future leader.

Elected as MP for Banff and Buchan in 1987, he quickly made his mark by getting himself banned from the Commons chamber for a week after interrupting the chancellor’s Budget speech in protest at the introduction of the community charge in Scotland.

When the job of party leader came up in 1990, Salmond made his move and won, perhaps surprisingly repositioning the SNP as more centrist, socially democratic and pro-European.

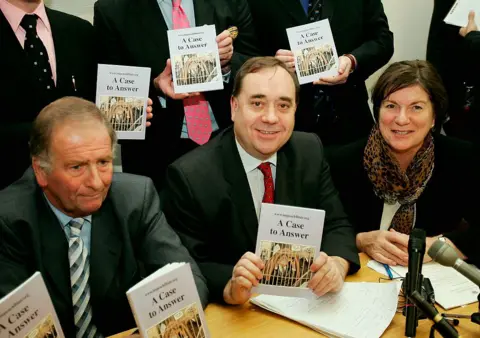

PA Media

PA MediaThroughout the 1990s, Salmond became a familiar figure on radio and television and a great favourite of the UK press.

An effective political analyst and communicator, he derided the Thatcher and Major governments before turning his criticism on New Labour and Tony Blair.

He also increased his command of the SNP. His grip over its senior members and processes was total.

He built close support from key comrades such as party chief executive Michael Russell and younger talents including Nicola Sturgeon, who would become his protege and eventual deputy.

Salmond led the party into joining the “Yes-Yes” campaign for a Scottish parliament, arguing the “gradualist” rather than “fundamentalist” approach to gaining independence.

The SNP came second at the inaugural Holyrood election in 1999 and Salmond appeared to enjoy the role of chief opposition leader.

A witty and brilliant debater, he did not always show the best judgement. As Nato planes bombed Serbia in retaliation for its attacks on Kosovo, he opposed the conflict because it was not authorised by a United Nations Security Council resolution.

Salmond described the Nato action as “an act of dubious legality, but, above all, one of unpardonable folly” and was heavily criticised for his comments.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn 2000, Salmond made the surprise decision to quit and stand down as both leader and MSP.

He returned to Westminster, a move which underlined a common criticism that the man calling for Scotland’s “freedom” was more at home in London.

But he was also in demand as an acute critic of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and the close personal and political relationship between UK Prime Minister Tony Blair and US President George W Bush.

Salmond was one of 11 MPs who attempted unsuccessfully to impeach Mr Blair. His actions, as well as his presence on marches and speeches at protests, made him a leading figure in the anti-war movement and won him many admirers.

But his absence from Edinburgh during this period was not good for his party.

John Swinney had succeeded him as leader, but stood down in 2004 following a string of dismal election results, criticism from across his party and the negative publicity of a leadership challenge.

As that summer progressed, there were persistent rumours that Salmond was considering a return.

He responded by borrowing a line from General William Sherman, who, on being asked to run for president following the American Civil War, declared: “If nominated, I’ll decline. If drafted, I’ll defer. And if elected, I’ll resign.”

Always partial to a dramatic flourish, Salmond announced he had changed his mind just before nominations closed, having cut a deal with candidate Nicola Sturgeon which saw her agree to be his number two.

He told journalists he was not just launching a campaign to be SNP leader, but his “candidacy to be first minister of Scotland”.

He promised to unite what had become a fractious Scottish parliamentary party, and focus on winning the 2007 election.

And that he did, by the narrowest of margins. He formed a minority government and relied on Green and Conservative support to get his manifesto through one vote at a time.

For the more radical elements of his party, this might have been seen as sleeping with the enemy. But Salmond recognised working across the chamber was both necessary and desirable.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHe was comfortable in the role of first minister and went about government in a measured, positive way. There was less of the smart-Alex of old and it was clear he took the job seriously.

Salmond had been in the role for just over a month when Islamist terrorists rammed the front entrance of the main terminal building at Glasgow Airport.

His handling of the crisis was met with acclaim and he worked closely with Gordon Brown’s government in London.

But over the coming few years there would be clashes over the decision to release the Lockerbie bomber, Abdelbaset al-Megrahi, and the handling of the financial crisis.

Salmond was accused of taking a “cavalier” approach to dealing with US tycoon Donald Trump’s £1bn Scottish golf resort.

An inquiry into the affair by Holyrood’s local government committee raised concerns over the Scottish government’s decision to call in the plans, following their rejection by Aberdeenshire Council, after “two five-minute phone calls”.

The probe concluded the decision, although unprecedented, was competent. It was a typical Salmond approach to problem-solving.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn many ways, 2011 marked the high point of Salmond’s political career. He pulled off what had always been descibed as the impossible – winning a majority at a Scottish parliamentary election.

A triumphant SNP began planning for an independence referendum.

Over the course of the following three years, Salmond was credited with out-smarting Prime Minister David Cameron and his coalition government colleagues, winning crucial battles over the timing and structure of the vote and the wording of the question which would be put to voters.

The official campaign was meant to take place in the autumn of 2014 but in reality the battle lasted the three-and-a-half years between election and referendum.

Rival campaigns were meant to take the debate out of the politicians’ hands but in the end it came down to Salmond trading blows with Labour’s Alastair Darling in a series of televised debates.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe FM was strong on rhetoric and vision, projecting an optimistic view of a future Scotland that could do anything it wanted; prosperous and fair, unshackled from the union with England but close to its European allies.

He was less sure on dealing with Scotland’s structural deficit, what currency would be used and how state pensions would be funded and paid.

In the end, the result was a “No” to independence.

Salmond had failed. That he had led his side to a 45% share was a remarkable achievement that provided little succour.

Within hours, he announced his resignation. Almost 60, it was time to hand over the fight to a younger generation. His close friend and loyal deputy Nicola Sturgeon was his chosen successor.

He chose to stand again for Westminster, winning Gordon as part of the SNP surge of 2015, when the party won 56 out 59 seats, significantly enhancing its power in the Commons.

But it was short-lived. He lost the seat just two years later, bringing to an end a political career spread more than 30 years and two parliaments.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe following years were sometimes awkward for his supporters and admirers.

His decision to host a chat how on RT, the former Russia Today channel editorially controlled by Vladimir Putin’s Kremlin, was a source of criticism and embarrasment to his party.

That was suspended in February 2022 in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. A year later a programme with the same format began broadcasting on Turkish public television.

There was an Edinburgh Fringe chat show in 2017 which included a rather crude innuendo about Theresa May, Nicola Sturgeon, Ruth Davidson and Melania Trump.

It prompted his successor as leader, Nicola Sturgeon, to comment that: “Occasionally Alex is not as funny as he thinks he is.”

It was a minor hint at tension between the two and the joke would look even more unfortunate in the light of what was to come later.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn August 2018 the Daily Record newspaper revealed Salmond had been reported to police over sexual assault allegations dating back to his time as first minister.

He denied the claims and said he was taking the Scottish government to court to challenge the complaints procedure which had been activated against him.

A week later he resigned from the SNP after 45 years. He said he wanted to avoid internal division within the party, which was facing calls to suspend him.

The subsequent parliamentary inquiry revealed that, in the nine or so months leading up to the initial story breaking, a complicated series of meetings and conversations had taken place between those at the top of the SNP and those at the top of the Scottish government, often confusing the division between the two.

Mistakes in the complaints process were such that in January 2019 Salmond won a judicial review, ruling the investigation was unlawful, unfair and “tainted by apparent bias”.

He was later awarded more than £500,000 in costs.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThat same month he appeared in court and was charged with 14 offences, including two counts of attempted rape. In 2020, after two weeks of evidence, he was acquitted of every charge.

But the testimony was devastating for his public image.

Salmond’s advocate, Gordon Jackson KC, admitted that his client had sometimes behaved badly, calling him “touchy-feely”.

Details of inappropriate behaviour included Salmond admitting having a “sleepy cuddle” with one complainer, and what Mr Jackson called “a bit of how’s your father” with another – both younger members of his staff, neither of them his wife.

The KC said in his closing speech that the former first minister “could certainly have been a better man”.

There was also confirmation of what had long been whispered; that Salmond could bully colleagues and staff. Witnesses called him “extraordinarily pugnacious” and “extremely demanding”.

Two subsequent inquiries into the conduct of ministers and officials saw Salmond asserting his belief that many in his former party had colluded against him in an effort to block any final return to frontline politics.

PA Media

PA MediaYet there was to be a final return, as leader of the newly-formed Alba party. Launched just ahead of the 2021 Holyrood election, it attracted a few defections from his old party but never achieved more than 3% at the ballot box.

Salmond never wavered from his belief that independence was necessary, desirable and inevitable for Scotland.

His enthusiasm for the cause did not extend to his former comrades in the campaign, however. He was often brutally critical of Nicola Sturgeon, Humza Yousaf and John Swinney, his one time proteges and friends who succeeded him into Bute House.

Away from politics, Salmond was something of an enigma. He and wife Moira, who never had children, closely protected their private lives.

He loved golf, football and horse racing and was said to be a keen reader.

Love him or loathe him, few would dispute Alex Salmond’s skill and achievements as a politician.

He never achieved his dream of independence but as one of the most talented politicians of his generation, he took the SNP as close to its goal as it had ever been.